Many critics argue that the penal system is a civil rights issue that disproportionately targets African Americans, marginalized groups and low income communities.

Since the 1970s, US criminal justice practices have shifted away from the rehabilitation model for convicted persons and adopted more punitive models of retribution. In addition, incarceration rates have skyrocketed. In an article for the Harvard Political Review, Liz Benecchi writes, “in the 1989 Supreme Court Case Mistretta v. United States, the Court upheld federal ‘sentencing guidelines‘ which removed rehabilitation from serious consideration when sentencing offenders. Defendants were sentenced strictly for the crime, with no recognition given to factors such as amenability to treatment, personal history, efforts to rehabilitate oneself, or alternatives to prison.”

Video clip courtesy of OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network

The inequalities permeating the criminal justice system and the implicit racial bias within its sentencing and policing practices have deep roots within the institutional practice of slavery. These collectively shape perceptions that continue to determine the fates of millions, in particular Black youth who—according to nationwide data in a report from The Sentencing Project—were “more than four times as likely to be detained or committed in juvenile facilities as their white peers.”

Black children who were enslaved on plantations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were denied the innocence of childhood. This notion morphed into a current-day adultification system of beliefs and practices that show up in how Black youth and those of other marginalized groups are overpoliced within the criminal justice and educational systems as well as in the larger society. In 2014, twelve—year—old Tamir Rice was throwing snowballs and playing with a toy gun in a neighborhood park when a resident called 911 dispatch to notify them of a “man” pointing a pistol. The call to Cleveland police ended in the death of Rice as police arrived at the park, shooting and killing him within two seconds of their arrival.

Video clip courtesy of OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network

A report published by Georgetown Law’s Center on Poverty and Inequality released in 2017, found that Black girls are seen as being more adult and less innocent than their white peers. Data collected during the study “Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood” found that “even in the age bracket of 5–9 years old, adults perceive Black girls as needing less nurturing, protection and comforting than white girls of the same age, and that they’re more independent.” The adultification of Black children not only denies them their youth but can have serious ramifications when negative racialized misconceptions are projected onto children, creating the perception that they are less innocent and therefore undeserving of compassion.

Barriers to Reentry

After serving his time in prison, Ralph Angel returns to St. Josephine and is surrounded with the support and love of his family members and community. He returns to the farm where he was raised and that he has known as his home. Even with strong familial connections, shelter and support, Ralph Angel struggles with returning to his community and has several brushes with offenses that could violate his parole and return him to prison. Like Ralph Angel, many parolees find themselves in a cycle of criminalization and incarceration. Of the 600,000 persons released from the criminal justice system in a given year, two-thirds will reoffend within three years, creating a cycle of punishment and offense. This is called recidivism, which is defined as “the re-arrest, reconviction or re-incarceration of an ex-offender within a given time frame.”

Furthermore, many formerly incarcerated persons are reintroduced into society with little to no resources, which makes a successful reentry close to impossible. Money, housing, food and clothing are necessities that play a critical part in whether or not someone will return to prison or be successful upon release.

“A person’s successful reentry into society can be viewed through how adequately they are able to meet six basic life needs: livelihood, residence, family, health, criminal justice compliance and social connections.”

— Ann Jacobs, director of the Prisoner Reentry Institute at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Released without Rehabilitation

Many states have also defunded programs that address mental health issues, educational attainment and work skills. States instead rely on punitive sentencing without rehabilitative services. This practice leaves the formerly incarcerated ill-prepared with the employment, educational, and social skills to transition into a society that has undergone significant advances while they were in prison.

Joan Petersilia said “there is a very simple and immutable ‘iron law of imprisonment’: Almost everyone who goes to prison ultimately returns home — about 93 percent of all incarcerated persons. (A relative handful die in jail; the rest have life sentences or are on death row.) Although the average incarcerated person now spends 2.5 years behind bars, many terms are shorter, with the result that 44 percent of all those now housed in state prisons are expected to be released within the year. This year, some 750,000 men and women will go home. Many — if not most — will be no better equipped to make successful, law-abiding lives for themselves than they were before they landed in prison.”

“The adaptation to imprisonment is almost always difficult and, at times, creates habits of thinking and acting that can be dysfunctional in periods of post-prison adjustment. Yet, the psychological effects of incarceration vary from individual to individual and are often reversible. To be sure, then, not everyone who is incarcerated is disabled or psychologically harmed by it. But few people are completely unchanged or unscathed by the experience. At the very least, prison is painful, and incarcerated persons often suffer long-term consequences from having been subjected to pain, deprivation, and extremely atypical patterns and norms of living and interacting with others.”

— Craig Haney

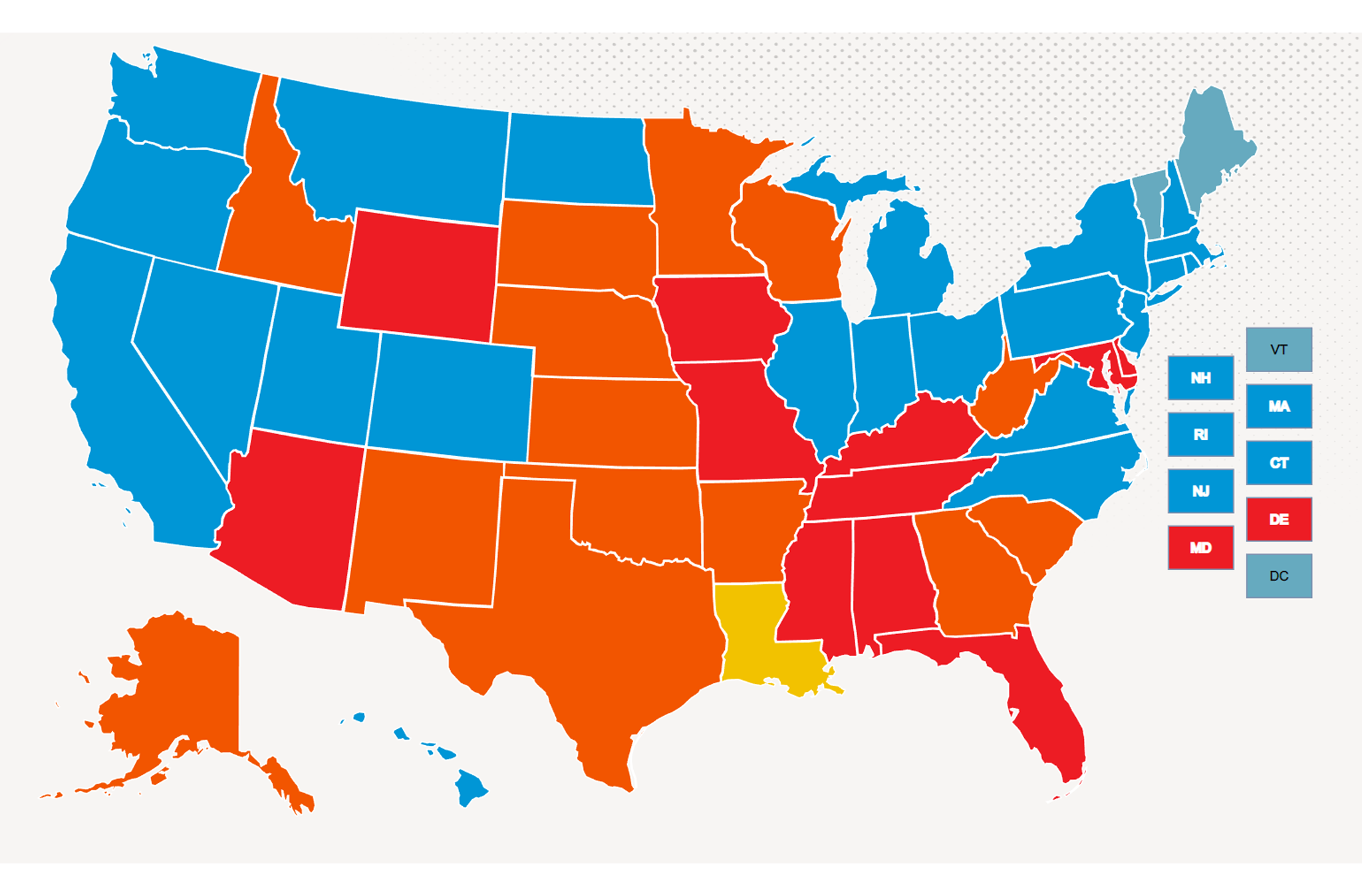

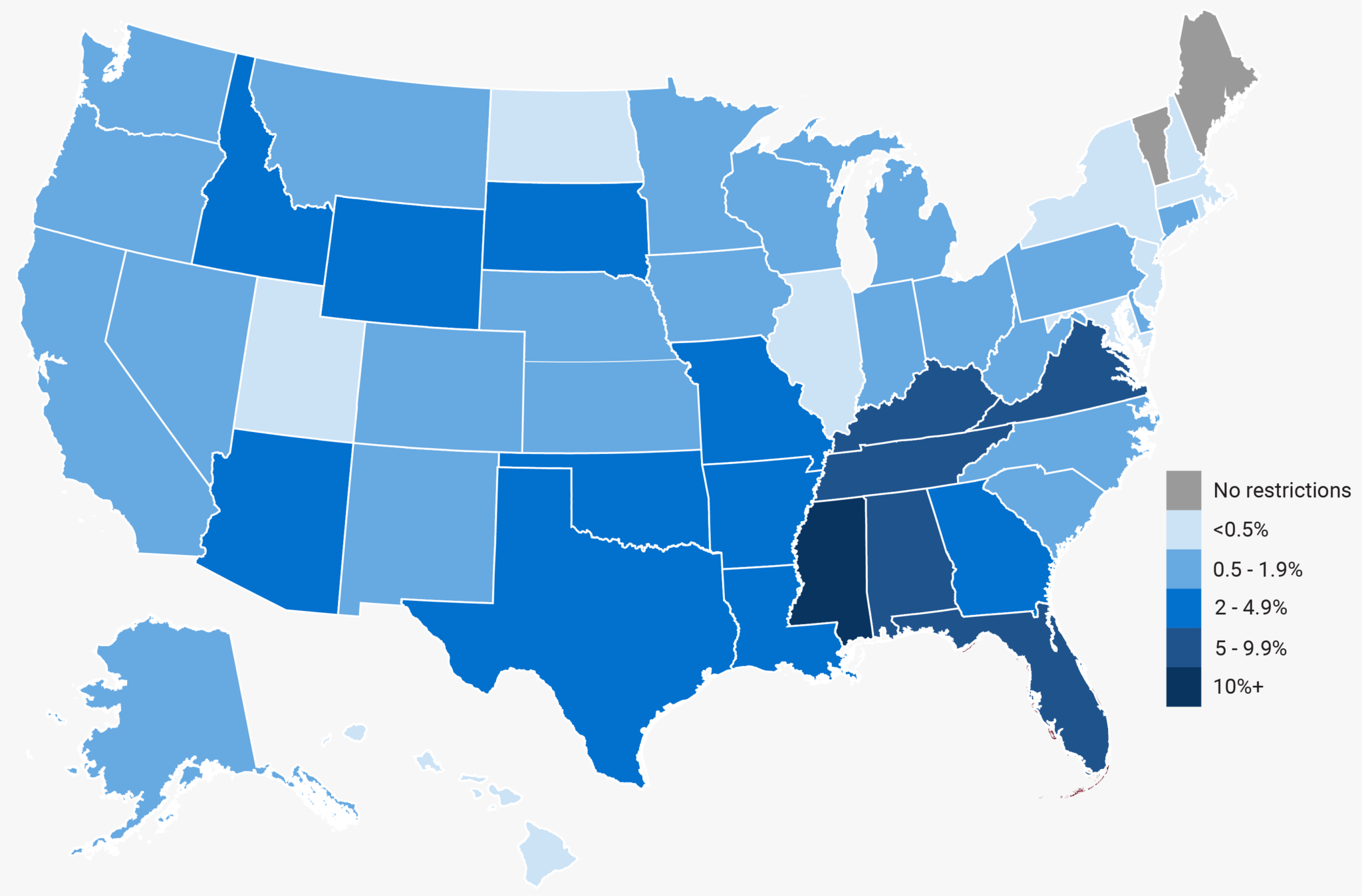

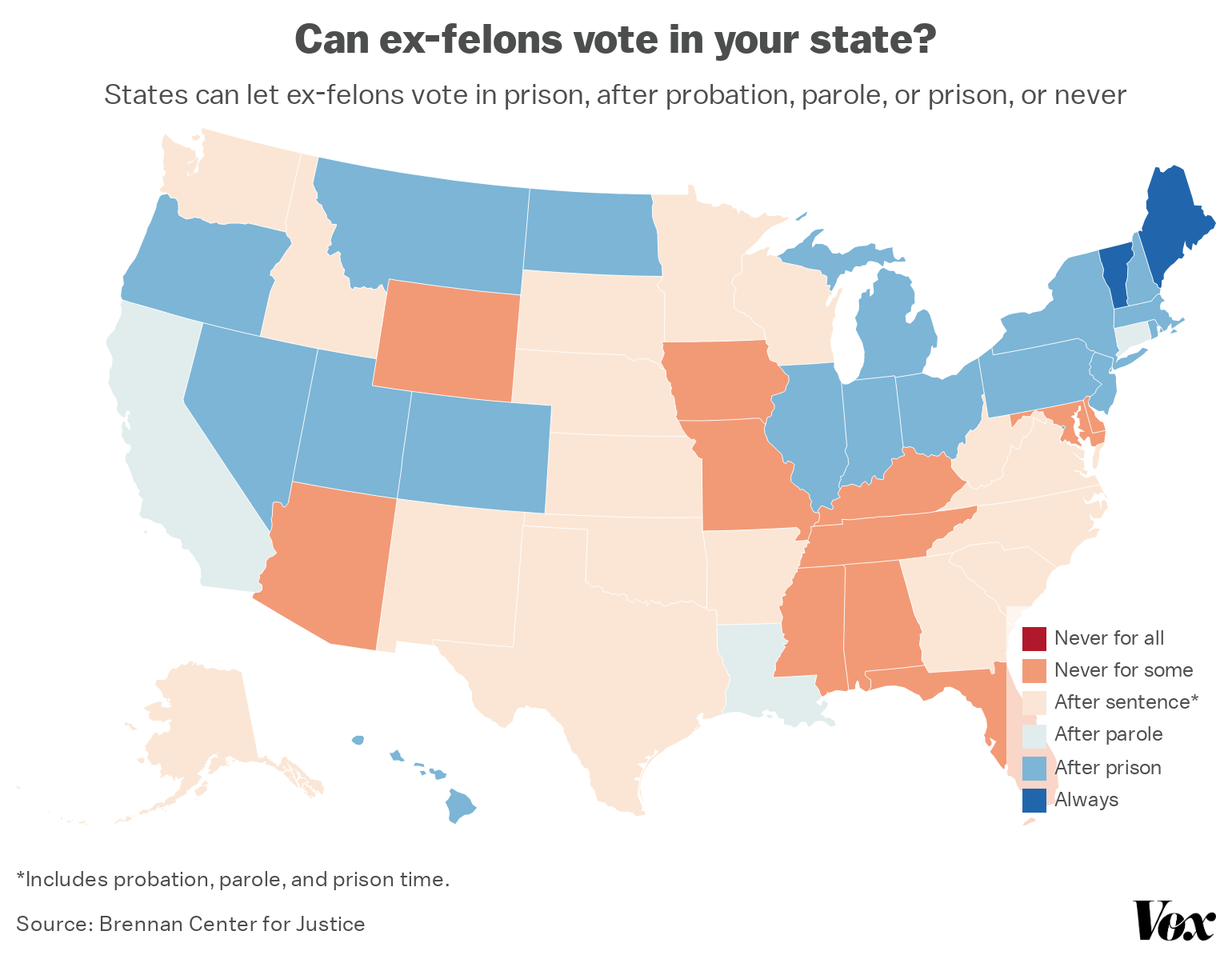

Although it has been established that voting is a constitutional right and is foundational to a democratic society, those who have “served their time” may be denied the right to vote. In 2020 alone, roughly 5.2 million Americans were unable to vote due to felony disenfranchisement laws. Their criminal convictions serve as barriers to this fundamental right. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, felony disenfranchisement laws keep millions of citizens from voting and are directly connected to Jim Crow laws.

In its early stages, disenfranchisement was introduced as a legal practice called “civil death” imposed against people who committed crimes within what were then British colonies. “Civil death,” which derived from ancient Greek, Roman, Germanic and Anglo-Saxon law, required offenders to relinquish all property and civil rights as punishment for crimes committed. A fledgling United States of America then adopted criminal disenfranchisement as the law of the land throughout the eighteenth century. Beginning with the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1792, each state passed its own version of disenfranchisement legislation.

Disenfranchisement for Black people was framed through the lens of slavery. Before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans were viewed as “property” and were not considered legal citizens of the United States. Until that time only white men could vote. It was not until July 9, 1866, with the passing of the Civil Rights Act and the ratification of the 14th Amendment, that formerly enslaved persons were granted “equal protection under the laws.” As the country began to rebound from the ravages of the Civil War, ideas of what an interracial democracy could look like began to take shape. The call for universal male suffrage, the ability to vote, grew. With the adoption of the 15th Amendment on February 3, 1870, formerly enslaved [men] and free people [men] of African descent were given the right to vote. The equal protection clause prohibited states from race-based disenfranchisement. Sections one and two of the 15th Amendment note:

“Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

However, the ratification of the 15th Amendment did not change the racist legislation of the states, which continued to disenfranchise Black men from voting through discriminatory practices such as poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses and brutality. Neither the Civil Rights Act of 1866 nor any constitutional amendments granted women of any race or ethnicity the right to vote in the United States. It was not until the passing, and later the ratification of, the 19th Amendment in 1920 that women were granted the right to vote within the United States.

Finally, during the Reconstruction period, African American men took to the ballot box and were elected as representatives in states throughout the South, such as Mississippi and Louisiana, with Alabama producing the highest percentage of Black office-holders. See chart to the right.

| State | Number of Officeholders |

| Alabama | 173 |

| Arkansas | 46 |

| District of Columbia | 11 |

| Florida | 58 |

| Georgia | 135 |

| Louisiana | 210 |

| Mississippi | 226 |

| Missouri | 1 |

| North Carolina | 187 |

| South Carolina | 316 |

| Tennessee | 20 |

| Texas | 49 |

| Virginia | 85 |

| Total | 1517 |

Tragically the actualization of freedom and democracy for African Americans was short-lived. The Federal Government withdrew its troops from the South along with its support for race-based equality programs such as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Black people were left unprotected in a confederacy of states still smarting from a crippling civil war loss. Southern states devolved into the purveyors of endless years of racial terror and brutalization against people of color.

The rate of lynchings) soared as white domestic terror groups used violence to maintain the social order of white dominance and intimidate Black men from exercising their right to vote. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that disenfranchisement state laws increased. The labor of the formerly enslaved transformed into convict leasing. As freedmen, they were overpoliced by restrictive and racist policies such as the Pig Laws and Black Codes. They began to fill prisons now housed on former plantation lands.

On August 12, 1890, more than a hundred men gathered in the Mississippi state capital for a constitutional convention. In his opening speech, Judge Solomon Saladin Calhoon, president of the convention, charged the delegates with a single task: “devise a way to keep Black men from voting in Mississippi. Let’s tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the universe. We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.“

“On April 24, 1877, as part of a political compromise that enabled his election, President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops from Louisiana—the last federally-occupied former Confederate state—just 12 years after the end of the Civil War. The withdrawal marked the end of Reconstruction and paved the way for the unrestrained resurgence of white supremacist rule in the South, carrying with it the rapid deterioration of political rights for Black people”

— EJI Reconstruction in America

Lawmakers in Mississippi targeted Black men through a number of tactics.

More than a century ago, Mississippi structured its statewide elections in this way to preserve white supremacy. The state’s white leaders adopted the electoral system when they redrafted the state constitution in 1890. They ditched the charter drafted during Reconstruction to protect multiracial democracy and replaced it with one designed to suppress Black political power. Every weapon in Jim Crow’s arsenal was deployed: The new constitution imposed literacy tests, poll taxes, criminal disenfranchisement provisions and more.

Though black voters outnumbered white voters in the state at the time, the 1890 constitution apportioned the state legislature to guarantee a majority of seats would be held by white lawmakers. That apportionment also affected the statewide election plan: Even if a Black-supported candidate received a majority of votes, it would be almost impossible for him to clinch victory by also capturing a majority of the state House of Representatives districts. Lawmakers in those districts would then be able to elevate the second-place candidate to the governor’s mansion.

Mississippi’s white leaders did not disguise their intentions. “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter,” James K. Vardaman, one of the constitution’s framers as well as a future governor and senator, once boasted. “Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics.”

"The effects were startling. In a 1965 federal voting-rights case against the state, the U.S. Supreme Court noted that 50 percent of qualified Black Mississippians were registered to vote before the new constitution’s adoption. By 1899, that number had dropped to 5 percent.” - Matt Ford, New Republic

Another tactic used in Mississippi was tying lifelong disenfranchisement to crimes more likely to be committed by Black people. These disenfranchisement laws are still on the books in Mississippi. On August 24, 2022, more than 132 years later, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals voted to uphold the disenfranchisement law passed on August 12, 1890. The court found that the “law was ‘steeped in racism,’ but said the State had made enough changes in the 132 years since to override its white supremacist taint.” As of 2018, nearly 1 of every 10 adults in Mississippi is disenfranchised due to a felony conviction—more than triple the national rate.