Throughout seven seasons of the series QUEEN SUGAR, audiences have witnessed many examples of ancestral religious practices drawn from indigenous African religions.

Throughout seven seasons of the series QUEEN SUGAR, audiences have witnessed many examples of ancestral religious practices drawn from indigenous African religions.

The truth of us is complicated. — Ava DuVernay

In QUEEN SUGAR, viewers are given a glimpse into Rootwork, also known as Conjure and Hoodoo.

The practice evolved from African spirituality and the Christian rituals that enslaved people encountered once they were stolen from their homelands.

Throughout seven seasons, Nova Bordelon performs rituals rooted in African traditions such as cleansings and blessings, signaling her connection to her ancestral roots and showing how the practices are used today.

Video clip courtesy of OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network

In QUEEN SUGAR, viewers are given a glimpse into Rootwork, also known as Conjure and Hoodoo.

The practice evolved from African spirituality and the Christian rituals that enslaved people encountered once they were stolen from their homelands.

Throughout seven seasons, Nova Bordelon performs rituals rooted in African traditions such as cleansings and blessings, signaling her connection to her ancestral roots and showing how the practices are used today.

Video clip courtesy of OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network

LESSON THREE

Introduction

Indigenous African Religions

New Orleans has long been a melting pot of races, religions, ethnicities and cultures. Arriving from various parts of Africa and the Caribbean, enslaved and free people of color in French-colonized New Orleans did not all share the same language or culture. Indigenous African religious practices, along with other pathways such as food, often drew the attention of early reporters and visitors to New Orleans, and in an attempt to invalidate and dehumanize people of color, these traditions were often sensationalized, casting Indigenous African religions as strange and uncivilized and perpetuating racist stereotypes about their practitioners.

In reality, these practices, passed down from generation to generation, were a resource for the communities they served. Yvonne Chireau, a professor of religion at Swarthmore College and author of Conjure and Christianity in the Nineteenth Century: Religious Elements in African American Magic, writes that “For its part, Conjure spoke directly to the slaves’ perceptions of powerlessness and danger by providing alternative—but largely symbolic—means for addressing suffering. The Conjuring tradition allowed practitioners to defend themselves from harm, to cure their ailments, and to achieve some conceptual measure of control over personal adversity.”

“The God described in the Bible is none other than the God who is already known in the framework of our traditional African religiosity. The missionaries who introduced the gospel to Africa in the past 200 years did not bring God to our continent. Instead, God brought them.”

— Dr. John Mbiti, Theologian

Nova Bordelon, and practitioners like her, know the importance of ancestral spiritual practices and ancestry. They recognize the spiritual world, human spirits and nature spirits.

Video clip courtesy of OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network

LESSON THREE

Introduction

Indigenous African Religions

New Orleans has long been a melting pot of races, religions, ethnicities and cultures. Arriving from various parts of Africa and the Caribbean, enslaved and free people of color in French-colonized New Orleans did not all share the same language or culture. Indigenous African religious practices, along with other pathways such as food, often drew the attention of early reporters and visitors to New Orleans, and in an attempt to invalidate and dehumanize people of color, these traditions were often sensationalized, casting Indigenous African religions as strange and uncivilized and perpetuating racist stereotypes about their practitioners.

In reality, these practices, passed down from generation to generation, were a resource for the communities they served. Yvonne Chireau, a professor of religion at Swarthmore College and author of Conjure and Christianity in the Nineteenth Century: Religious Elements in African American Magic, writes that “For its part, Conjure spoke directly to the slaves’ perceptions of powerlessness and danger by providing alternative—but largely symbolic—means for addressing suffering. The Conjuring tradition allowed practitioners to defend themselves from harm, to cure their ailments, and to achieve some conceptual measure of control over personal adversity.”

“The God described in the Bible is none other than the God who is already known in the framework of our traditional African religiosity. The missionaries who introduced the gospel to Africa in the past 200 years did not bring God to our continent. Instead, God brought them.”

— Dr. John Mbiti, Theologian

Nova Bordelon, and practitioners like her, know the importance of ancestral spiritual practices and ancestry. They recognize the spiritual world, human spirits and nature spirits.

Video clip courtesy of OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network

Slave Ship Aurore

Meet a group of vibrant scuba divers determined to find, document and positively identify slave shipwrecks.

Source: National Geographic

Collectively, indigenous African religions – like many others – help people explore enduring questions of life:

- Why am I here?

- How did I get here?

- What is my purpose in life?

- Is there a Higher Power?

- What is death and what happens when I die?

Though diverse in many ways, indigenous African religions help people form a worldview to understand the world in which they live. This worldview is a system of attitudes, practices, beliefs and values that govern and shape its people. More than anything, indigenous African religions are not primitive or savage.

Collectively, indigenous African religions – like many others – help people explore enduring questions of life:

- Why am I here?

- How did I get here?

- What is my purpose in life?

- Is there a Higher Power?

- What is death and what happens when I die?

Though diverse in many ways, indigenous African religions help people form a worldview to understand the world in which they live. This worldview is a system of attitudes, practices, beliefs and values that govern and shape its people. More than anything, indigenous African religions are not primitive or savage.

Biloxi, Mississippi

Slave Ship Aurore

Charting the Journey

Between 1719 and 1731, the Company of the Indies oversaw the purchase and forced transatlantic transportation of more than 6,700 Africans from West and West Central Africa to Louisiana. Much of the city’s population were enslaved people from Africa, but there were also people from France, Spain, the Caribbean, Latin America and many other countries.

The city’s location along the mighty Mississippi River proved beneficial to its tremendous cultural and economic growth. Its various waterways formed a useful and well-traveled transportation route for moving crops and goods. It was also a system of intercommunication for early residents. Tobacco and indigo were exported from New Orleans initially; it became a major port for cotton later. In addition to importing rice and vegetables, New Orleans became, for a time, the largest center for selling enslaved Africans in the nation.

“The first eight slave ships bearing Africans to Louisiana dropped anchor at the ports of Dauphin Island and Biloxi. (Both towns were part of the Louisiana colony until 1763.) New Orleans saw its first direct arrival in 1723, when the Expédition offloaded some eighty-eight enslaved captives purchased in Senegambia onto a plantation across from New Orleans on the Mississippi River’s west bank (now part of the Algiers Point neighborhood). This plantation—like the slave trade—was operated by the Company of the Indies.”

— 64 Parishes.org

Charting the Journey

Between 1719 and 1731, the Company of the Indies oversaw the purchase and forced transatlantic transportation of more than 6,700 Africans from West and West Central Africa to Louisiana. Much of the city’s population were enslaved people from Africa, but there were also people from France, Spain, the Caribbean, Latin America and many other countries.

The city’s location along the mighty Mississippi River proved beneficial to its tremendous cultural and economic growth. Its various waterways formed a useful and well-traveled transportation route for moving crops and goods. It was also a system of intercommunication for early residents. Tobacco and indigo were exported from New Orleans initially; it became a major port for cotton later. In addition to importing rice and vegetables, New Orleans became, for a time, the largest center for selling enslaved Africans in the nation.

“The first eight slave ships bearing Africans to Louisiana dropped anchor at the ports of Dauphin Island and Biloxi. (Both towns were part of the Louisiana colony until 1763.) New Orleans saw its first direct arrival in 1723, when the Expédition offloaded some eighty-eight enslaved captives purchased in Senegambia onto a plantation across from New Orleans on the Mississippi River’s west bank (now part of the Algiers Point neighborhood). This plantation—like the slave trade—was operated by the Company of the Indies.”

— 64 Parishes.org

Code Noir

Although French colonial slavery granted more rights to enslaved Africans than British or Dutch territories, it was still a brutal system. Enslavers realized they could not prevent the enslaved population from gathering. Because the enslaved population outnumbered their captors, enslavers instituted the Code Noir (Black Code) in 1724, tightly controlling the movements of the enslaved population.

“The God described in the Bible is none other than the God who is already known in the framework of our traditional African religiosity. The missionaries who introduced the gospel to Africa in the past 200 years did not bring God to our continent. Instead, God brought them.”

— Dr. John Mbiti, Theologian

Code Noir

Although French colonial slavery granted more rights to enslaved Africans than British or Dutch territories, it was still a brutal system. Enslavers realized they could not prevent the enslaved population from gathering. Because the enslaved population outnumbered their captors, enslavers instituted the Code Noir (Black Code) in 1724, tightly controlling the movements of the enslaved population.

The Haitian Revolution

“During a now legendary ceremony, men and women made a pact to end their enslavement no matter the cost. The result would be the most successful slave uprising in the history of the world.”

— Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Black Church

The Haitian Revolution was one of the strongest displays of African ancestral spirituality.

Enslaved people in Saint-Domingue, colonized by France, collaborated with free people of color. They gathered in the Haitian mountains to carefully plan a powerful rebellion that was ultimately led by the charismatic general, Toussaint Louverture.

Religion and religious practices were an important tool in the emancipation movement. It allowed for the exchange of political and cultural ideas that could not be expressed openly by the enslaved.

Haitian Vodou was a powerful social force that unified the enslaved population giving them the courage and strength to overthrow the French and gain their independence. Haitian Vodou was a blending of the indigenous African religions of enslaved Africans from Central and West Africa (including Yoruba, Fon and Kongo people). This process of blending, combining, or merging different beliefs, religions, or schools of thought is called syncretism. In time Louisiana Voodoo, also known as New Orleans Voodoo, arose. It too was created through syncretism. It is a melding of the Vodun, indigenous African religions, Catholicism, Freemasonry, and Haitian Vodou.

The Haitian Revolution

“During a now legendary ceremony, men and women made a pact to end their enslavement no matter the cost. The result would be the most successful slave uprising in the history of the world.”

— Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Black Church

The Haitian Revolution was one of the strongest displays of African ancestral spirituality.

Enslaved people in Saint-Domingue, colonized by France, collaborated with free people of color. They gathered in the Haitian mountains to carefully plan a powerful rebellion that was ultimately led by the charismatic general, Toussaint Louverture.

Religion and religious practices were an important tool in the emancipation movement. It allowed for the exchange of political and cultural ideas that could not be expressed openly by the enslaved.

Haitian Vodou was a powerful social force that unified the enslaved population giving them the courage and strength to overthrow the French and gain their independence. Haitian Vodou was a blending of the indigenous African religions of enslaved Africans from Central and West Africa (including Yoruba, Fon and Kongo people). This process of blending, combining, or merging different beliefs, religions, or schools of thought is called syncretism. In time Louisiana Voodoo, also known as New Orleans Voodoo, arose. It too was created through syncretism. It is a melding of the Vodun, indigenous African religions, Catholicism, Freemasonry, and Haitian Vodou.

Congo Square

In 1817, New Orleans Mayor Augustin de Macarty issued a decree that restricted gatherings of enslaved people to one open plot bordered on three sides by St. Anne Street, N. Rampart Street, and St. Peter Street at the Place des Nègres. Eventually, this plot would come to be known as Congo Square. Congregating in Congo Square, both enslaved and free Creoles of color danced, played music, sold food and other goods and practiced the otherwise suppressed African elements of their syncretic Catholic West African religion. Since its inception as a gathering place for people of color, Congo Square has featured drumming. Enslaved people carried their ancestral heritage with them using performative practices such as singing, dancing and drumming to recall and document their religion in complex and sophisticated ways wherever they were taken.

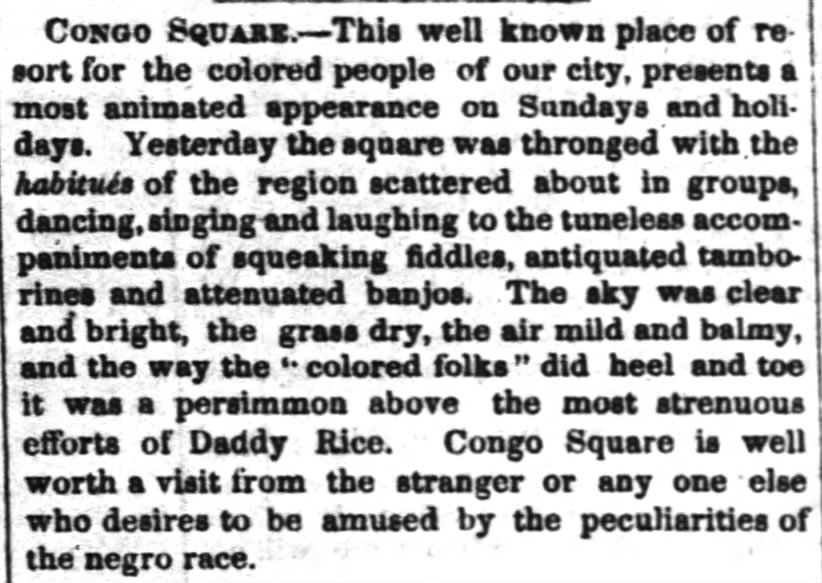

This 1848 newspaper article from the Times-Picayune encourages visitors to New Orleans to stop on Sundays to experience music and dancing. The reference to “Daddy Rice” in the article compares the enslaved community’s talent to a well known white performer of the time who gained notoriety performing in blackface.

Melville and Frances Herskovits, anthropologists of African and African diaspora culture, describe the importance of tribal drumming in Suriname: “The drums have more than a musical significance in this culture [inferring the culture of the town and bush people of Suriname]. Tradition assigns to them the three-fold power of summoning the gods and the spirits of the ancestors to appear, of articulating the messages of these supernatural beings when they arrive, and of sending them back to their habitats at the end of each ceremony. Both in Town and in the Bush, the dancers who are the worshippers—one of the most important expressions of worship is dancing—face the drums and dance toward them, in recognition of the voice of the god within the instruments.”

As in the towns and villages of Suriname, the sound of the African drums could be heard in Congo Square, enabling enslaved men and women to communicate with and honor their ancestors, acting as an important tool that sustained their cultures and identities. The blend of races, cultures and nationalities from different corners of the globe, which began early in the eighteenth century, resulted in the unique music, language, traditions and religious practices of New Orleans.

It is possible to imagine, given what we know about Nova’s mother and the Lavoisier family in QUEEN SUGAR, that members could have participated in the activities of Congo Square.

Image courtesy of ARRAY

Congo Square

In 1817, New Orleans Mayor Augustin de Macarty issued a decree that restricted gatherings of enslaved people to one open plot bordered on three sides by St. Anne Street, N. Rampart Street, and St. Peter Street at the Place des Nègres. Eventually, this plot would come to be known as Congo Square. Congregating in Congo Square, both enslaved and free Creoles of color danced, played music, sold food and other goods and practiced the otherwise suppressed African elements of their syncretic Catholic West African religion. Since its inception as a gathering place for people of color, Congo Square has featured drumming. Enslaved people carried their ancestral heritage with them using performative practices such as singing, dancing and drumming to recall and document their religion in complex and sophisticated ways wherever they were taken.

This 1848 newspaper article from the Times-Picayune encourages visitors to New Orleans to stop on Sundays to experience music and dancing. The reference to “Daddy Rice” in the article compares the enslaved community’s talent to a well known white performer of the time who gained notoriety performing in blackface.

Melville and Frances Herskovits, anthropologists of African and African diaspora culture, describe the importance of tribal drumming in Suriname: “The drums have more than a musical significance in this culture [inferring the culture of the town and bush people of Suriname]. Tradition assigns to them the three-fold power of summoning the gods and the spirits of the ancestors to appear, of articulating the messages of these supernatural beings when they arrive, and of sending them back to their habitats at the end of each ceremony. Both in Town and in the Bush, the dancers who are the worshippers—one of the most important expressions of worship is dancing—face the drums and dance toward them, in recognition of the voice of the god within the instruments.”

As in the towns and villages of Suriname, the sound of the African drums could be heard in Congo Square, enabling enslaved men and women to communicate with and honor their ancestors, acting as an important tool that sustained their cultures and identities. The blend of races, cultures and nationalities from different corners of the globe, which began early in the eighteenth century, resulted in the unique music, language, traditions and religious practices of New Orleans.

It is possible to imagine, given what we know about Nova’s mother and the Lavoisier family in QUEEN SUGAR, that members could have participated in the activities of Congo Square.

Nova:

“Were all the women in our family called to be healers?”

Martha:

“Yes, but not all accepted it.”

Enslaved Africans in early Louisiana, disoriented and separate from the homeland and their people, did what they have always done, sought ways to connect, communicate and create. They found comfort in practicing the common elements of their Indigenous African religions and ancestral religious practices.

In QUEEN SUGAR, this tradition is shown being passed on to Trudy Bordelon and Nova Bordelon along with their cousin Martha Lavoisier. At times, Nova engaged in practices that would characterize her as a healer, an herbalist and sometimes a diviner.

- Nova—as a healer—realized that illness is spiritual at its core. Such illnesses require spiritual remedies.

- Nova—as an herbalist—engaged in ongoing training on the proper ways to harness the divine healing resident in everything from bark to berries, roots to fruits.

- Nova—as a diviner—made direct contact with the spiritual realm to understand what is happening in the spiritual and how it can inform what is happening in the natural world.

Nova:

“Were all the women in our family called to be healers?”

Martha:

“Yes, but not all accepted it.”

Enslaved Africans in early Louisiana, disoriented and separate from the homeland and their people, did what they have always done, sought ways to connect, communicate and create. They found comfort in practicing the common elements of their Indigenous African religions and ancestral religious practices.

In QUEEN SUGAR, this tradition is shown being passed on to Trudy Bordelon and Nova Bordelon along with their cousin Martha Lavoisier. At times, Nova engaged in practices that would characterize her as a healer, an herbalist and sometimes a diviner.

- Nova—as a healer—realized that illness is spiritual at its core. Such illnesses require spiritual remedies.

- Nova—as an herbalist—engaged in ongoing training on the proper ways to harness the divine healing resident in everything from bark to berries, roots to fruits.

- Nova—as a diviner—made direct contact with the spiritual realm to understand what is happening in the spiritual and how it can inform what is happening in the natural world.

Inherited Knowledge

Nova’s spiritual practice of Rootwork has been passed down through her mother and cousin who are both healers.

The word inheritance is usually associated with material possessions but not all the treasures we inherit are monetary.

We can also inherit knowledge, customs and traditions related to our family, community or culture. These practices and knowledge and their related objects and artifacts are sometimes called intangible cultural heritage or living heritage. Although these traditions may sometimes not occupy physical space, they are a part of the living heritage of a place and therefore hold an important role not only for individual families, but for groups and larger distinctive communities too. Living heritage is described as the practices, expressions, knowledge and skills that communities, groups and sometimes individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.

Source: Discover South Carolina

Learn: Intangible Cultural Heritage

In 2003, UNESCO established a convention to safeguard intangible cultural heritage, which includes knowledge and practices, as well as the related “objects, artifacts, and cultural spaces.” The goal is to help spread awareness in order to preserve these activities, which can encompass dance, specialized language/jargon, jokes, cuisine, crafts, dress, celebrations, local traditions and lore, stories, songs and traditional architecture.

In this activity, learners will identify, research, connect, process and reflect on their family or community traditions and use creative tools to construct a lasting record of the legacies from their ancestors.

Identify

- the traditions you share as a family or community.

- how your family or community marks or recognizes birthdays and other individual celebrations.

- how your family or community recognizes national holidays, cultural holidays and religious holidays.

Research

- What traditions are unique to our family or community? What do we do that is unlike other families?

- What are some legacy traditions that we still use today (things that our family or community have done for generations)?

- What are some traditions that you hope we keep doing for generations to come—and why?

- What are some traditions that you hope we stop doing—and why?

Collect

- audio recording with clips of the interviews

- video recording with clips of the interviews

- a photo essay of images of family members practicing the tradition

- a soundtrack of original music

- a slide deck with words and images documenting a tradition

- a website or a blog with clips of the interviews as well as words and images documenting a tradition

Source: UNESCO

Reflection Questions

- What draws us to rituals and traditions? How might rituals and traditions help us to learn about ourselves?

- What are some traditions that you wish to revive or launch as a way of building community within your family?

- How often—or infrequent—is God or the concept of a higher being present in your family’s traditions?

- How often—or infrequent—are your elders, matriarchs, patriarchs and ancestors celebrated or honored in your family’s traditions?

- To what extent do your family’s traditions include elements of indigenous African religions and ancestral religious practices?

- To what extent do your family’s traditions promote the security and well-being of you, your family and your community?

- What did you learn about the spiritual practices of enslaved people?

Take a look at how the Bordelon family honors the lives of those they’ve lost.

New generations are finding solace and healing in reconnecting with the practices of their ancestors and reconnecting with traditions that honor their ancestors and lineages. Check out the videos that follow to learn more.

Additional Resources

Black Magic Matters:

Hoodoo as Ancestral Religion

Meet The Entrepreneurs Using African Spirituality To Create Businesses

New Orleans Voodoo

(A Virtual Tour)

This lesson is presented in several modules. Use your desktop or tablet to go deeper with QUEEN SUGAR into these lessons and activities.