LESSON 1: MODULE 1

Introduction

What impact did sugarcane farming have on the eighteenth-, nineteenth- and twentieth-century Louisianian and American economies?

As Black landowners in Louisiana’s fictional St. Josephine Parish, the Bordelon family lives on what is historically known as Louisiana’s River Road, a 70-mile stretch of land that winds along both banks of the Mississippi River from Baton Rouge to New Orleans. What are now modern homes, farmland and factories were once successful plantations cultivated by slave labor. Much of QUEEN SUGAR is filmed on the St. Joseph Plantation, in the city of Vacherie, in St. James’s Parish.

Louisiana’s Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism divides the state into five cultural regions — Sportsman’s Paradise, Crossroads, Cajun Country, Greater New Orleans and Plantation Country, the last of which begins in Pointe Coupee Parish, north of Baton Rouge, and goes as far south as St. James Parish, the actual location of QUEEN SUGAR’s fictional St. Josephine Parish.

Called Cabahonnoce by the Spanish and Tabiscana or Bayougoula Village by the French, Vacherie is a French term meaning cowshed or cattle ranch. Records from Louisiana State University show that “Before the coming of the white man, this region was the homeland of the Houmas (Reds) and the Chitimachas Indian Nations.” Planter and rancher Joseph Blancpain purchased land in the area in 1740 specifically for that purpose: to develop a cattle ranch. Decades later, these lands along the Mississippi River and surrounding parishes became sugarcane plantations. Current day residents of Vacherie, which would include QUEEN SUGAR’s fictional Bordelon family, are faithful to their roots. According to the 2000 census, “Vacherie Louisiana is the least transient place in the whole country. Ninety-eight percent of the citizens here were born in Louisiana, while nationally, only about 60% of Americans live in the state where they were born.”

“Stories tell of a time when Indians hunted buffalo on the banks of Bayou Terre aux Boeufs, south of present-day New Orleans. Documented memories recall ancient cypress forests so thick you could not see the sun. Houmas (Indians) celebrated their annual Corn Harvest near the site of what would become Congo Square.”

— Monique Verdin, Unfathomable City, A New Orleans Atlas

Bordelon

Timeline

of Events

Vacherie, Louisiana was homeland of the Houmas (Reds) and the Chitimachas Indian Nations

First slave ship arrives in Louisiana.

Landry family owns the Bordelon family.

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Congo Square becomes meeting place for the city's enslaved after an ordinance is issued by the mayor.

12,000+ Free people of color living in New Orleans.

Angel Bordelon is born.

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Queen Sugar

South Louisiana is sugarcane country; in the nineteenth century, if cotton was considered king, sugar was queen. Sugarcane, which is a Caribbean crop, flourished in Louisiana’s hot and humid environments and moist soil. Sugarcane was first introduced to the state by Jesuit priests in 1751. According to historian Freddi Williams Evans, author of Congo Square: African Roots in New Orleans, these priests “brought cane seed from Santo Domingo along with forty enslaved Africans who knew how to cultivate the crop.”

The first sugarcane plantation in Louisiana with enslaved people as the cultivators was owned by Etienne Debore, whose plantation was located in present-day Audubon Park in New Orleans. Debore benefited from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804): as exiled sugar makers sought refuge in New Orleans, Debore leveraged their skills into a profitable industry.

Courtesy of L.J. Schira/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

More plantation owners, much like QUEEN SUGAR’s fictional Landry family, began growing sugarcane after the United States acquired the territory from the French as a part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The crop was labor-intensive and large numbers of enslaved Africans were purchased to do this notoriously brutal and often deadly work. The crushed cane was used for fuel, molasses and as a base for rum. The industry grew rapidly, and by 1830, New Orleans had the largest sugar refinery in the world, with an annual capacity of 6,000 tons. Louisiana became the nation’s sugar-growing capital, earning the nickname “sugar bowl,” which lives on in the college football bowl game played in New Orleans each year.

“Rising up in the midst of the verdure are the white lines of the negro cottages and the plantation offices and sugar-houses which look like large publice edifaces in the distance.”

— W.H. Russell, 1863

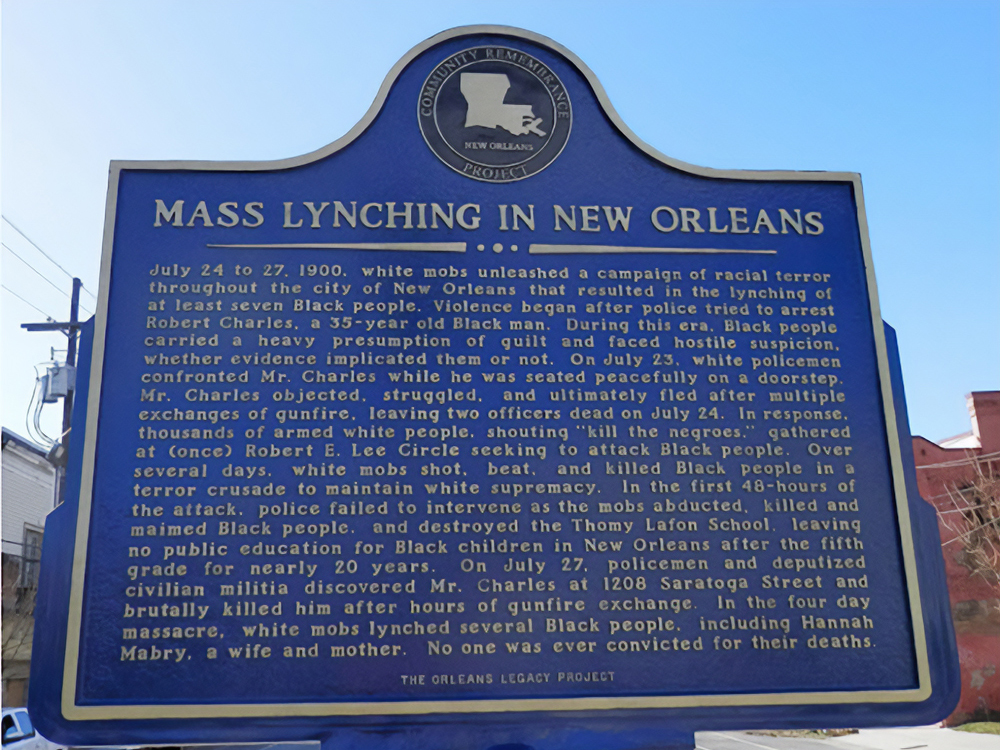

Sugarcane is an agro-industrial crop, meaning it is grown, harvested and cultivated all in the same place, without need to ship it off for further processing. Tremendous amount of human power and extreme labor would have been necessary to operate a sugarcane plantation in the 1700s and 1800s before modern-day farming tools. The harsh labor alongside the constant threat of accidents, work related deaths, disease and climate also make sugarcane plantations the most dangerous type of plantation to work. During enslavement, to send someone south, or down the river to work on a sugarcane plantation was a death threat, and millions of enslaved people who had been a part of such a labor monopoly did not survive long enough for their stories to be heard.

Senegambia to Nouvelle-Orléans

Plantations are controversial and contentious landscapes because of their central role in developing systems of oppression like enslavement and because plantations expanded the economic wealth of the United States. The exploitation of enslaved laborers in southern Louisiana included people taken from the Senegambia region of Africa during the International Slave trade and later their descendants born into the internal U.S. domestic slave trade. QUEEN SUGAR’s fictional farm in St. Josephine Parish sits on and is adjacent to real-life plantations that exploited slave labor, mainly from the western African geographic region of Senegambia (current day Senegal and Gambia) during the Colonial Period of Louisiana (1718–1803).

The Senegalese Influence on New Orleans Culture and Cuisine

Brutal human bondage made the plantation system possible, leaving a legacy of injustice and inequality, which has influenced patterns of land use and development; and class and cultural divisions for centuries.

Tulane University professor Emily Clark writes, “[t]he connections between New Orleans and Senegal began in the early eighteenth century, when thousands of captives were transported from their homeland in Senegambia, today’s Senegal, to become slaves in the French colony of Louisiana. Two thirds of the enslaved men, women and children forced to immigrate to Louisiana during the colony’s French colonial era (1699–1769) came from this region of Africa.” The Senegambian people played a role in shaping the economy, the landscape and the culture of Louisiana and its capital city of New Orleans, ensuring Senegambia’s permanent imprint on the Gulf South. Notably, the Senegambian contributions of music helped New Orleans to become the birthplace of Jazz.

Creole Houses at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation, c. 1906, Thibodaux, Lafourche Parish, LA.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

What would life have been like on and around the Landry plantation? Plantations were a composite entity of activities: land, buildings and people subsisting within a hierarchy, with enslaved people fulfilling a multitude of roles, including farming, domestic work, carpentry and blacksmithing. As such, plantations were not monoliths; they had specific functions and purposes, often resulting in distinct features and layouts which varied based on the crops that were grown.

When French leaders established the colony of Louisiana in 1699 and later designed its capital of New Orleans in 1718, their hope was to make money with tobacco, rice and indigo cultivation. In writing about the technological savvy of the enslaved, scholar Freddi Williams Evans says, “the Africans brought agricultural and technological skills that helped to provide sustenance for everyday survival.” By 1732, the idea of tobacco had failed, and French colonists were dying at a much faster rate than enslaved Africans, causing the colony’s population to represent twice as many enslaved residents as French.

“One type of plantation could be distinguished from another by its barns, mills and other gear,” writes Fredrick Law Olmstead in The Cotton Kingdom. Olmstead goes on to describe their differences: “The identity of a tobacco plantation was marked by distinctive tobacco barns used to cure the leaves before they were packed into huge barrels. Standing in the yards of most cotton plantations were both a gin house and press for compacting processed lint into bales. By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, rice plantations often had large steam-powered mills to complement the older threshing platforms and winnowing houses where slaves had previously refined rice by hand. The mills located on Louisiana’s sugar plantations were large sheds, sometimes as much as three hundred feet long, containing boilers, engines, conveyor belts, rollers and evaporators. Because these mills spewed clouds of smoke and steam as the cane juices transformed first into syrup and then into raw sugar, it is not surprising that sugar plantations were said to resemble New England factory towns.”

Plantations and Preservation

Examining the plantation landscape through the perspective of the enslaved communities that built, labored and cultivated the land allows learners to understand that the enslaved people also perceived, experienced and shaped the spaces around them therefore the loss of even one of their homes is significant. Preserving these cabins continues to be an important part of documenting and presenting a fuller narrative of the families who once inhabited them, illustrating the enduring legacy and history of Black contributions not only to the landscape but to the development of the United States as an economic force on the global stage.

In Season 3, Episode 9 of QUEEN SUGAR (“The Tree and the Stone Were One”), Micah and his friends visit a plantation and are angered when they see a historical reenactment celebrating the antebellum period. Protesting the plantation’s interpretation, the young activists sneak back onto the plantation at night, lighting candles to commemorate the enslaved who had lived and died there. Their efforts, however, cause more damage than good.

ACTIVITY

Fact and Fiction

Who Gets to Tell the Story?

For this activity, imagine that the St. Josephine farmer’s Co-Op has encouraged Ralph Angel to open the Bordelon Farm for tours. Funds will raise awareness and money to support the area’s Black farmers.

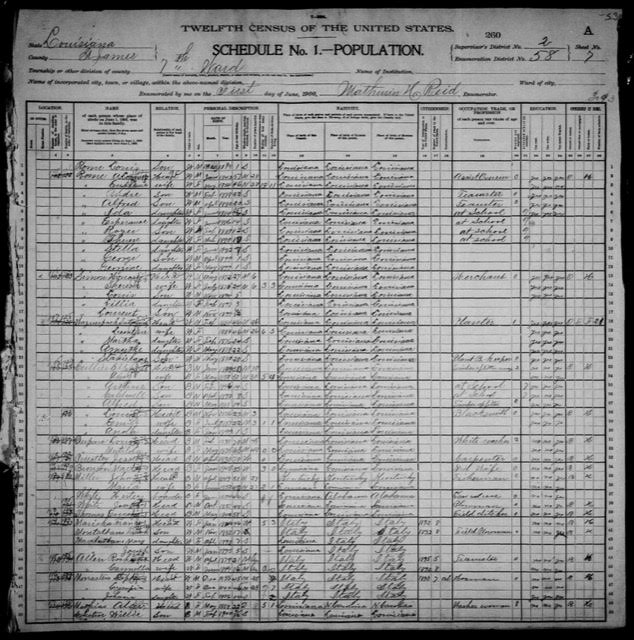

Fact: QUEEN SUGAR was filmed at a working sugarcane plantation that has been in operation since the early 1800s. On the land where the Bordelon family would have worked, between 1820 and 1830, Louis Scionneaux began building the St. Joseph Plantation. According to the 1840 United States Census, Scionneaux is listed as the owner of four slaves: one adult female between the ages of 36 and 54 and three children, two boys and one girl, all under the age of 10. The “big house” still stands on the grounds of the plantation, as well as multiple slave cabins.

Fiction: The Bordelon farm is the site of a mass burial of Black farmworkers from the 1887 Thibodoux Massacre, thus making it a historical site.

You are a new tour guide at this historic site and you need to write a script for your first tour. First, however, you will need to become familiar with the history of the property. It’s really important that your tour is accurate and interesting.

STEP 1: Watch and Read

- Watch your “orientation video” from Historian Ja’el Gordon, an expert on plantation history in southern Louisiana.

- Read Amanda Holpuch’s article, “Do Idyllic Southern Plantations Really Tell the Story of Slavery?”

Reflection Questions

- What did you learn about plantations from the historian? What information is new to you?

- Where do you see fiction and fact overlap? How is the Bordelon Farm like the St. Joseph Plantation? What are the differences?

- What stories are not being told by St. Joseph Plantation and other real-life plantations?

- How might you influence or convince plantations that offer tours to revise their scripts to share authentic stories based on facts?

- Should events like parties and weddings be held on plantations that were previously farmed by the enslaved? If your answer is no, what other locations in your city or state do you believe should also be off limits due to their history?

Courtesy of ARRAY

The St. Joseph Plantation and Manufacturing Company chronicles the history, origin and evolution of the sugarcane plantation:

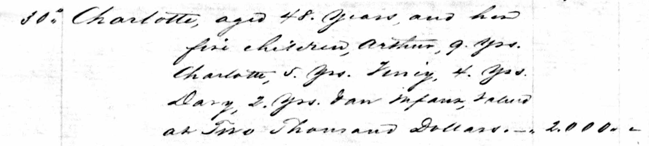

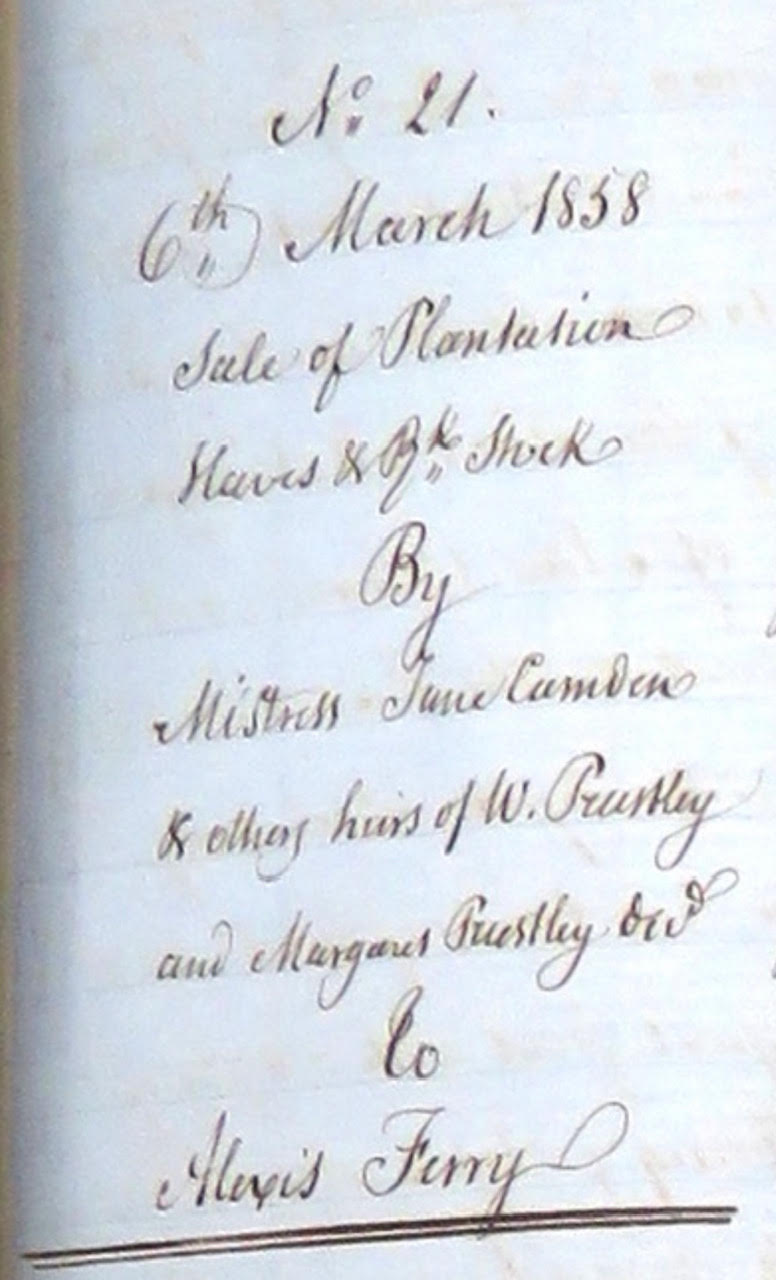

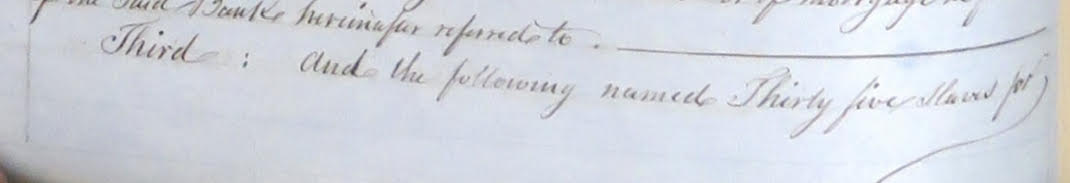

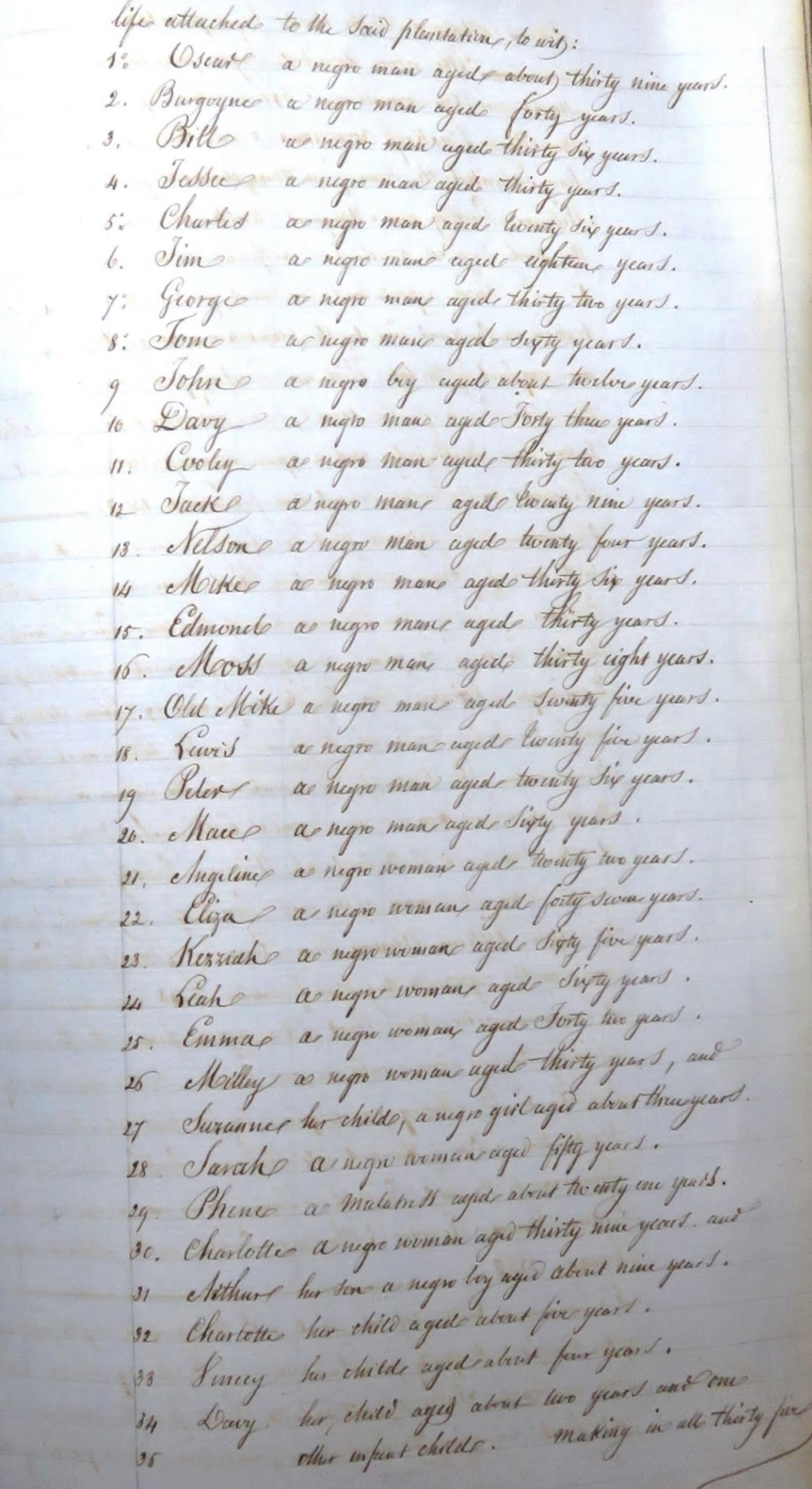

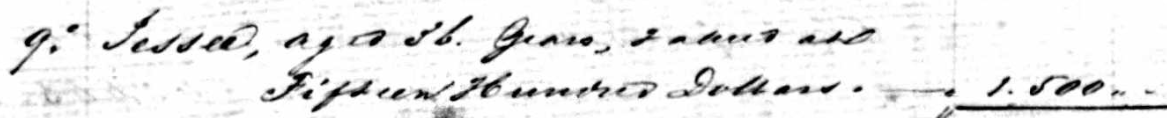

William Priestley and his family lived at the property after the Scionneaux’s; Margaret Priestley’s succession record in 1858 shows that the slaves and plantation were sold to Alexis Ferry (funded by Valcour Aime) collectively. Ferry remodeled the home, added four rooms and enclosed the ground floor to create a basement, where open space had previously sheltered the horse-drawn buggy that Mericq used to visit his rural patients.

Know Their Names

Let’s take a look into the lives of the men, women and children who served as craftspersons, engineers, scientists, architects, chefs and medical practitioners on the St. Joseph Plantation.

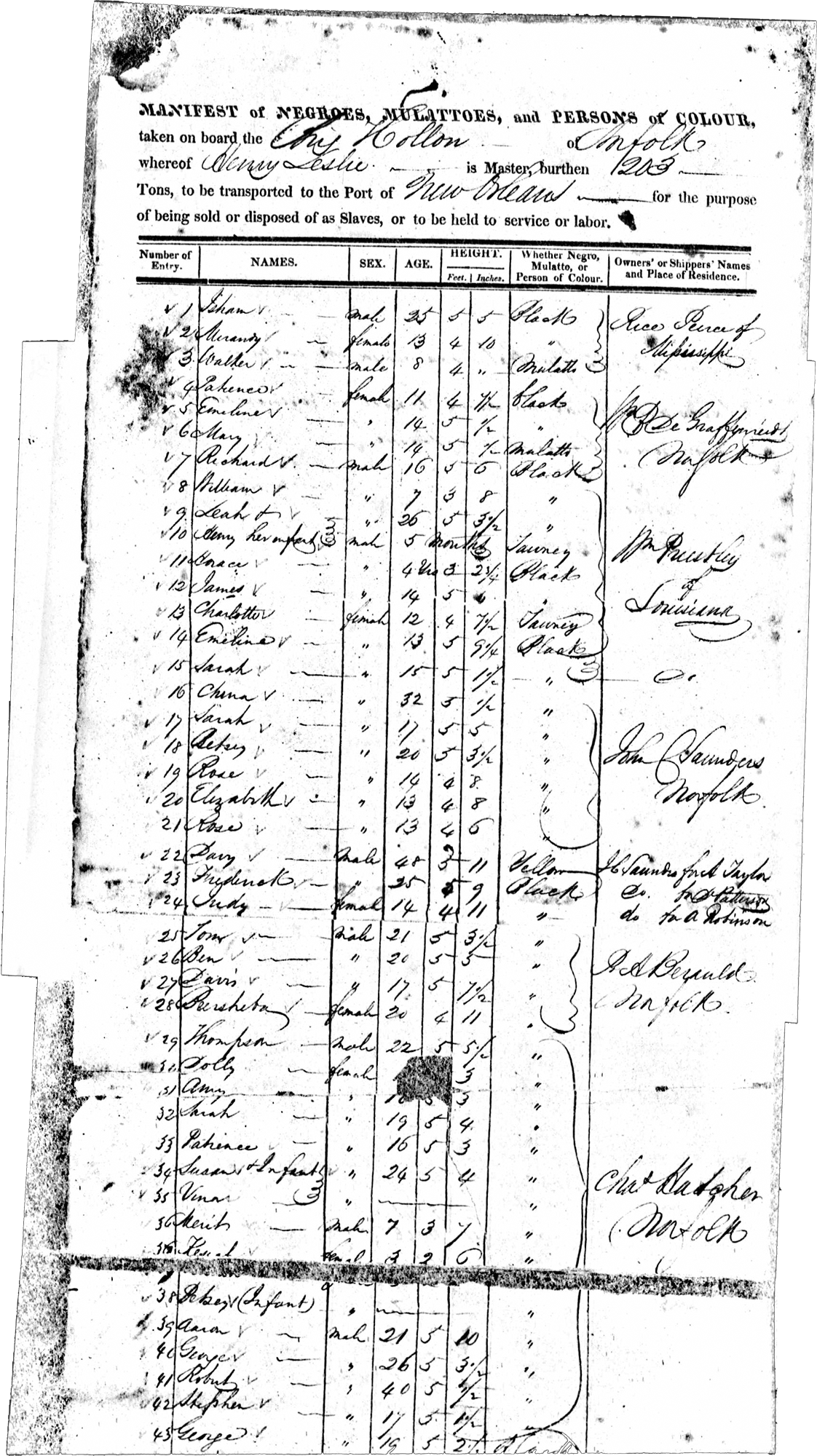

STEP 1: Examine the slave ship manifest

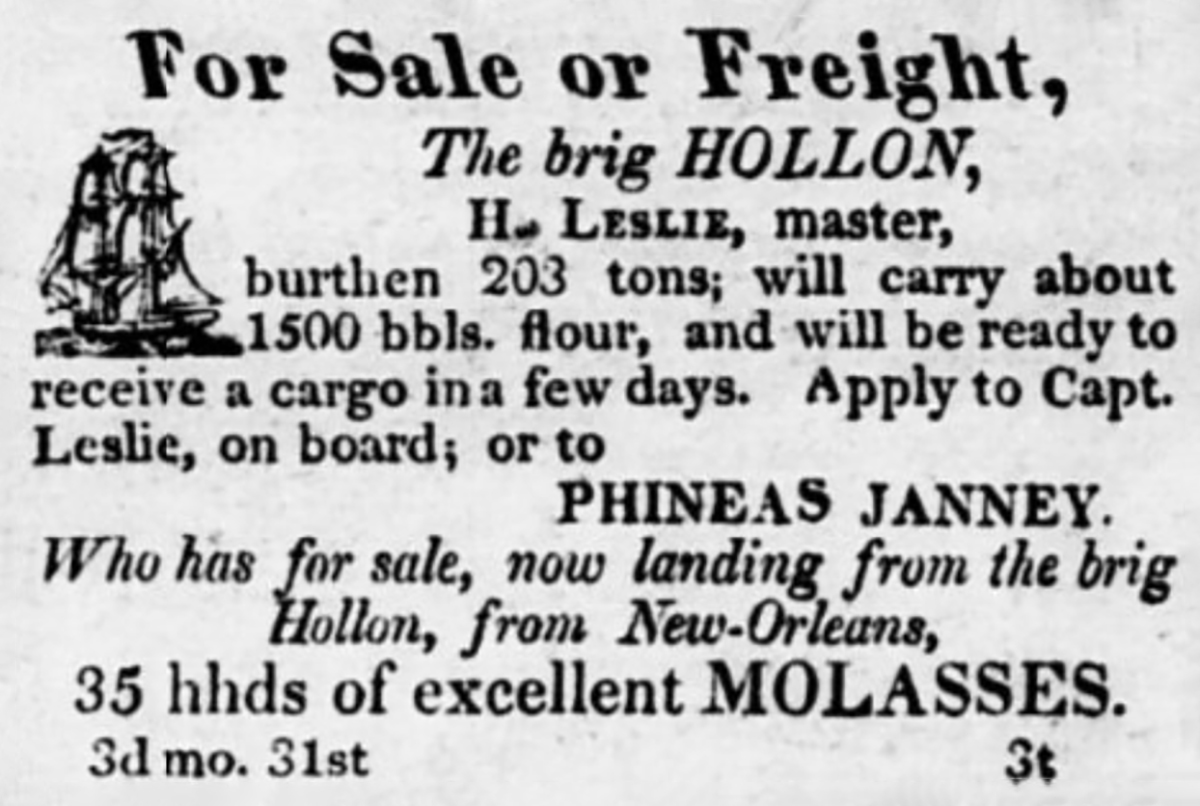

On October 22, 1825, the Brig Hollon departed the port of Norfolk, Virginia for its intended destination of New Orleans, Louisiana where several men would be anxiously awaiting its arrival. Aboard was human cargo – 87 individuals, both adults and children, sold “down the river” to the state’s harsh sugarcane parishes. On November 14, 1825, the ship docked in New Orleans and the collector signed off on the ship manifest verifying that the number of slaves that arrived matched the number of those who were shipped.

- Read the information at the top of the document. What information does the manifest contain about each passenger?

- One of the owners who awaited the arrival of the ship was William Priestley. Priestley was the second owner of what is now St. Joseph Plantation and the ship manifest shows that he was to take possession of seven enslaved individuals on the ship.

Leah, age 26; 5ft. 3in.; Black

Henry (Leah’s infant,) age 5 months; Tawny

Horace, age 4; 3ft. 2 ¾ in.; Black

James, age 14; 5ft.; Black

Charlotte, age 12; 4ft. 7 ½ in.; Tawny

Emiline, age 13; 5ft. 9 ¼ in.; Black

Follow the Records, Follow the People

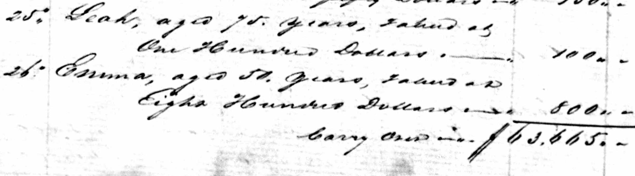

Legally, enslaved people were considered property, and though at times difficult to trace, records of the enslaved do exist in various government repositories. One such common document wherein enslaved people can be found is one that we still use today: a succession record. A succession record is a recorded listing of all properties, movables (including slaves) and other assets owned by a deceased individual at the time of death. Enslaved persons owned would be appraised according to their craft, gender, health, ability to have children and even their temperament. A succession record also discloses any debts owed and how a person’s assets and properties should be partitioned and distributed, all of which would be delegated by the courts.

At the time of her death, Margaret Priestley owned 30 individuals over the age of 12 and six children under the age of 10 who are listed with their respective mothers. Enslaved people listed on succession records were often identified by name, age, possible ailments, their skill or duties (i.e., le commandeur/driver, craftsman, seamstress, cook, sick nurse, domestic/house servant, field laborer, etc.) and their appraisal price. Margaret’s succession record did not provide information regarding their skills, duties, or positions on the plantation.

Lesson One: Legacy of the Land

Take a journey with QUEEN SUGAR‘s Bordelon family and follow their generational fight to keep the land of their forefathers.