LESSON 1: MODULE 4

Introduction

Plantation landscapes are dynamic spaces. Their legacy and function changed over time and generations, from slave plantations to post-plantation agricultural spaces. Their inhabitants changed from enslaved laborers to emancipated people, to sharecroppers and tenants, day laborers and landowners.

The wealth and capital created by the exploitation of enslaved people shaped the structure of property and power in the United States. It established a system of highly unequal land ownership that has persisted over centuries and continues today.

EXPLORE this interactive timeline highlighting important milestones as they relate to Black Americans and farming.

Land Ownership and Inequalities:

The Legacy of Sharecropping

With the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the end of the Civil War in 1865, more than four million enslaved people were freed, with many seeing land ownership as a critical aspect of their freedom and a pathway to prosperity.

The 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery resulted in the need for a different system of labor for agricultural production. Plantation owners found themselves without workers. Although Black people ceased to be owned, assuming the newly acquired identity of freedmen without property, money or a place to call home made for an unsustainable life. The system that emerged, with the assistance of local landowners and governments, was sharecropping and tenant farming.

To access the labor force that had produced their crops, enslavers subdivided and leased their land to the formerly enslaved. The landowners allowed a tenant to farm the land in exchange for a share of the crop. In addition to leasing the land, sharecroppers rented supplies and equipment from the landowners or other merchant stores on credit in order to work the land. Come harvest time, sharecroppers were required to give as much as half of their harvest to landowners as rent for the land.

On its face, sharecropping could have appeared to be a mutually beneficial arrangement. But in actuality, many freed slaves continued to work on white plantations, incurring debt on rented equipment and supplies using a credit system that charged excessive interest rates and benefited and advantaged white landowners. Most sharecroppers did not have any disposable income left, even after they had sold their share of the crop. If harvests were poor, sharecroppers remained in debt to the landowners and stores until the next year. Laws favoring landowners made it difficult or even illegal for sharecroppers to sell their crops to others besides their landlord—which meant they couldn’t earn a competitive rate—or prevented sharecroppers from moving if they were indebted to their landlord. This debt cycle tethered sharecroppers to the land they were working. While legally they were freedmen and women, in this system many Black people couldn’t become fully “free,” as they remained beholden to white land owners. Through sharecropping, white landowners hoarded the profits of Black workers’ agricultural labor, trapping them in poverty and debt, and obligating them to work their land for generations.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Sharecropping on St. Joseph Plantation

In June 2022, the National Park Service interviewed St. James Parish native and artist Reginald Roussell (b. 1959), who discussed memories of his childhood at St. Joseph Plantation.

Roussell’s grandmother’s cabin still stands on the St. Joseph Plantation property, which serves as the site of Ralph Angel’s farm in QUEEN SUGAR. With the help of historian and genealogist Ja’el Gordon, Roussell uncovered his own familial connections to the elders he remembered from the plantation. Both of his parents were also raised on the property. Roussell, an artist, has drawn sketches from memory of what he remembers from his childhood; his sketches include cabins that no longer exist due to wear and tear, time, movement and destruction.

Take a look at the National Park Service’s National Center for Preservation Technology and Training’s 3D laser scan of the St. Joseph Plantation cabins, including Roussell’s grandmother’s cabin which is the middle cabin

ACTIVITY

Using Freedmen’s Contracts to Understand Slavery after Emancipation

Let’s take a closer look at artifacts and resources from the Freedmen’s Bureau to explore what life was like for the Bordelon family and other families post-slavery. Along the way, compare and contrast enslavement with life after emancipation.

STEP 1: Watch and Read

- Watch clips from Freedmen’s Bureau and Connecting Roots: Freedmen’s Records

- Read Searching The Freedmen’s Bureau Records

STEP 2: Take Action

- Volunteer as a transcriber of Freedmen’s Bureau documents to learn more about the lives of formerly enslaved men and women. Here are resources to help you get started:

STEP 3: Research Using Freedmen Agreements

The Freedmen’s Bureau documents titled “Agreement with Freedmen” show newly freed men and their plantation owning employers. Jesse is listed as the fourth freedman on the agreement while his former owner Alexis Ferry is still listed as his employer.

- Within the written passage on the record, what stipulations and provisions are listed in the contract for each of the workers? In other words, how many days off are they allotted? How much will they be paid?

- What could be a reason a newly freed person would continue to work on the plantation property on which he or she was previously enslaved?

Image: Freedmen’s Bureau “Agreement with Freedmen,” February 6, 1865

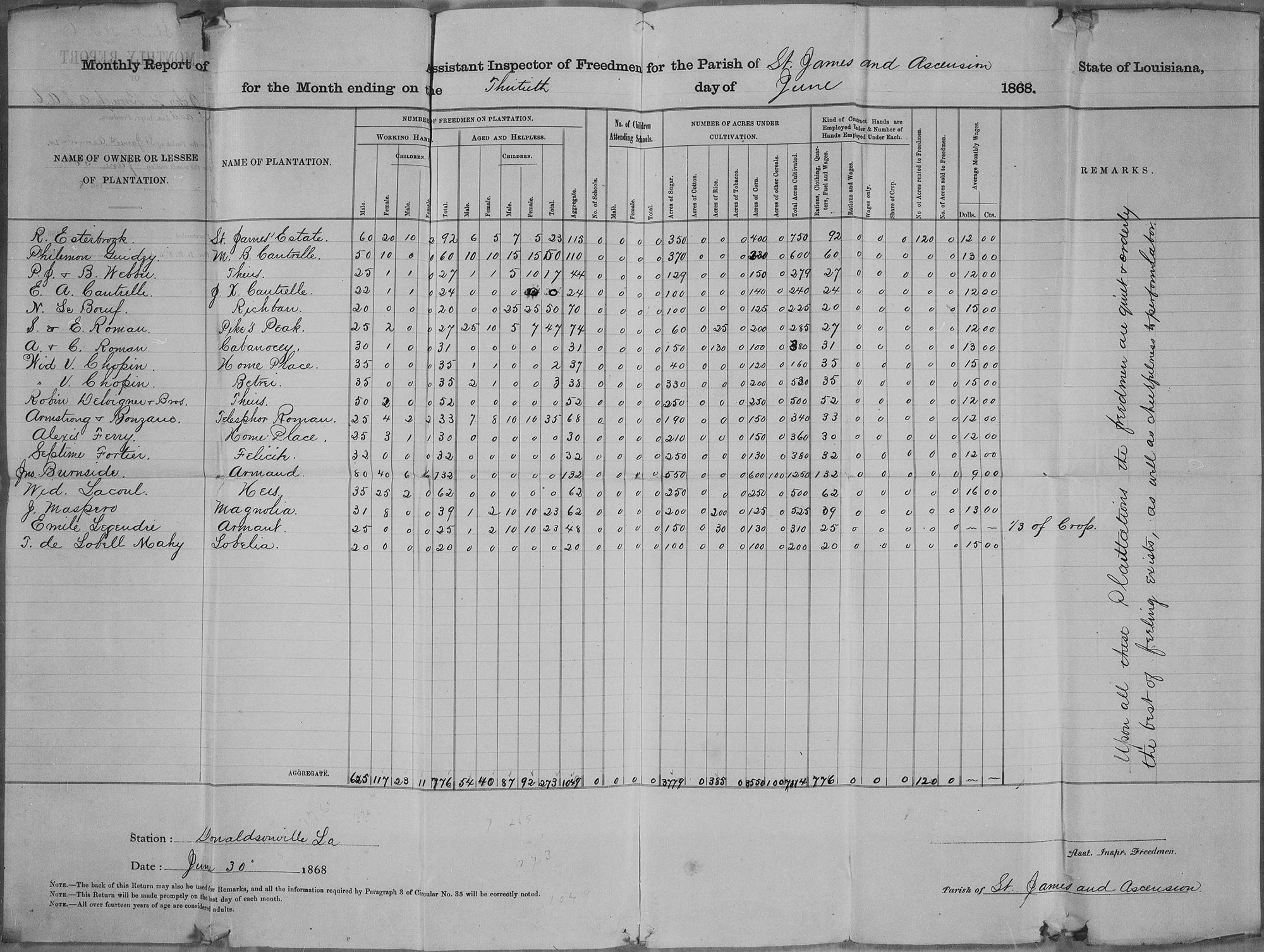

STEP 4: Research Using Plantation Owner Monthly Reports

The second set of Freedmen’s Bureau documents are the plantation owners’ monthly reports that show the number of freed persons (men, women and children) that were employed and the totals for the acreage of land that was cultivated. Records for Alexis Ferry’s plantation, which he called Home Place, are included in this report dated June 13, 1868.

Examine the report.

- What is the average age of a freedman working as a sharecropper?

- The column reporting the number of children attending school shows 0 for all plantation owners. What year was the first school for African American children documented in St. James Parish, Louisiana?

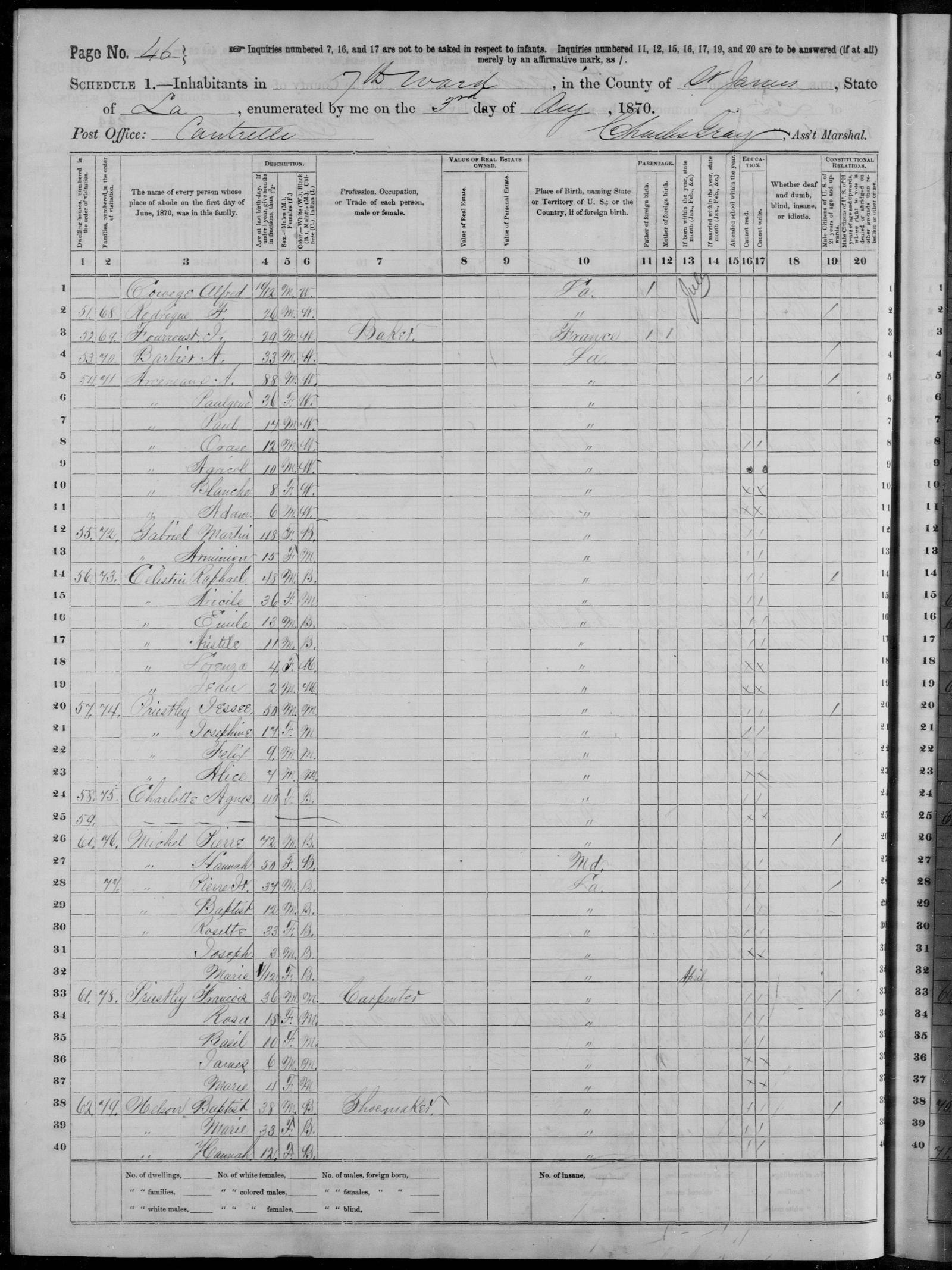

STEP 5: Research Using the 1870 and 1880 Census

The 1870 United States Census is the first census record that listed formerly enslaved African Americans and their families as people with names. Look closely at these two documents, an 1870 census record and an 1880 census record. Find the name Jesse Priestley.

- What are some of the differences between questions asked on the 1870 census vs those asked on the 1880 census?

- On the 1880 census, Jesse’s occupation was listed as carpenter. What occupations are documented for both of his sons?

- In what county and state do they live?

- What could have influenced his sons’ decision to seek jobs that were not typically held by freedmen in rural Louisiana during this time?

1880 Federal Census Record

Watch the video, then continue with this lesson.

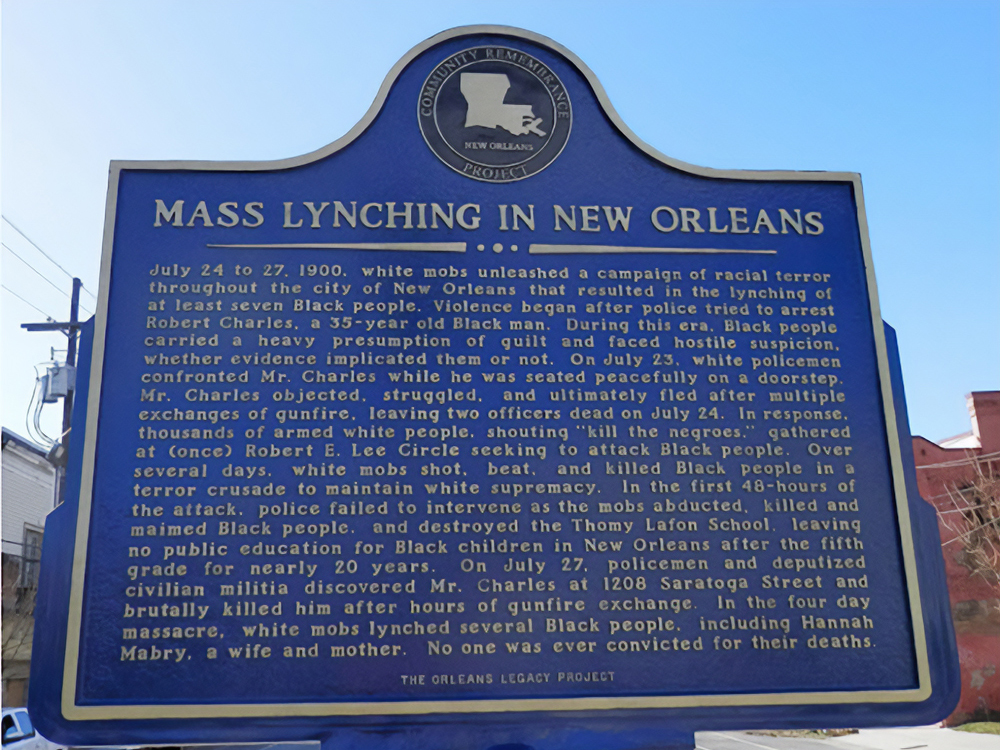

In season 3 of Queen Sugar, viewers see the Landry’s attempting to use eminent domain to build a prison right in the middle of St. Josephine’s Parish. The prison is a cruel symbol that calls back to the cycle of enslavement of Black people via a loophole in the 13th Amendment that resulted in the practice of convict leasing.

While the amendment formally abolished slavery throughout the United States, it included the caveat, “except as punishment for crime.” A person could not be the property of another, but the policy maintained a system of incarceration that, per its design, continues to enslave Black people.

Black Farming and Land Ownership Today

In spite of the many obstacles to land ownership, many Black families were able to acquire land and gain a greater sense of freedom and independence, and their land would be gradually transferred from relative to relative for generations, as a safe haven to raise families and farm. Ripped away from their countries and ancestral lands, Africans in America created spaces for themselves in a place that had stolen so much from them and built a new legacy of land. Generations had lived on the land, farmed it, and died for it. Although Black identity has become associated with the urban, a connection to the landscape is also an important aspect of Blackness. Unlike slave owners who saw the swamps and borderlands as uninhabitable and valueless, enslaved and free people of color often viewed the lack of oversight and harsh conditions of this terrain as an opportunity to eke out their own spaces. This previously undesirable land would later be stripped from Black owners as predatory developers targeted absentee owners of properties or inconsistencies in the public records to claim ownership.

By the turn of the twentieth century, former slaves and their descendants had amassed 14 million acres of land. Black agriculture was a powerhouse; per capita there were more Black farmers than white farmers. But by the turn of the twenty-first century, 90 percent of that land was lost.

Black farmers—then and now—continue to face more challenges than white farmers as a result of a multitude of “legal” tactics used to dispossess Black farmers of their land. To this day, Black farmers are frequently denied access to credit and struggle to compete with their white counterparts when they don’t have equal access to federal relief funding necessary to keep up with the pace of agricultural modernization. Additionally, practices such as eminent domain and disproportionate property tax levies have been used to force tax foreclosure sales.

Additional Resources

Why aren’t there more Black farmers in the United States?

“Farmer essentially meant white.” Black farmers, historians and generational land owners discuss the past, present and future of farming.

How southern Black farmers were forced from their land.

The majority of land lost by or stolen from Black farmers in the United States has occurred since 1950. The Atlantic calls this The Great Land Robbery. Learn more about how the lack of loans from the federal government and voting rights helped to push Black farmers off their land.

How Property Law is used to appropriate Black land.

Black Americans acquired a significant amount of property after the Civil War in areas that were not considered prime real estate. Most of that land has now been lost and VICE News’ Alzo Slade explores the vulnerability of Black landowners in the South.

Lesson One: Legacy of the Land

Take a journey with QUEEN SUGAR‘s Bordelon family and follow their generational fight to keep the land of their forefathers.