LESSON 1: MODULE 3

Introduction

Following Emancipation, America braced itself as the formerly enslaved chose to move to all parts of the United States in search of a sense of place, economic opportunities and belonging. Two well known migrations are the Exodus of 1879, which was the first mass migration of African Americans after the Civil War, and the Great Migration, which began in the early 1900s. Queen Sugar’s Charles Bordelon, father of Ernest and Aunt Vi, was a part of the second migration when he moved to Chicago around 1920 and then sent money back to Louisiana so that his family could by the farm. Let’s explore both migrations and their impact on land and legacy for Black Americans.

Bordelon

Timeline

of Events

Landry family land is intact - Bordelon family does not own property..

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

The U.S. Supreme Court delivers the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, affirming the Louisiana state law that mandated segregation.

Queenie Bordelon born

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Charles Bordelon moves to Chicago. He sends money 'back home' to his father Angel in St. Josephine, Louisiana.

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Angel Bordelon lynched by Landry family

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Ernest Bordelon born

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrates William Frantz Public School in New Orleans

Ernest Bordelon serves in the Vietnam War

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Ernest and Aunt Vi both hold the deed to the Bordelon family farm

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

Nova Bordelon born

*From the television series QUEEN SUGAR

“I was leaving the South to fling myself into the unknown… I was taking a part of the South to transplant in alien soil, to see if it could grow differently, if it could drink of new and cool rains, bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth of other suns and, perhaps, to bloom.”

— Richard Wright

To Transplant in Alien Soil

The Great Migration

Between 1915 and 1976, more than six million Black people, including QUEEN SUGAR’s Charles Bordelon, father to Ernest and grandfather to Charley, Nova and Ralph Angel, left the sugarcane fields, cotton fields, rice plantations and tobacco farms of the South during a seventy-year period known as the Great Migration.

Black people moved from rural areas in the South to northern cities like Chicago, Detroit, New York and west to places like Los Angeles and Seattle. They left as families or went alone. They traveled by car, train, bus and by foot. Some were sent for, while others went ahead, securing a home and a job in anticipation of reuniting with relatives or friends. Whatever the route or procedure, there was one common denominator that caused the mass exodus: the treacherous stronghold of Jim Crow.

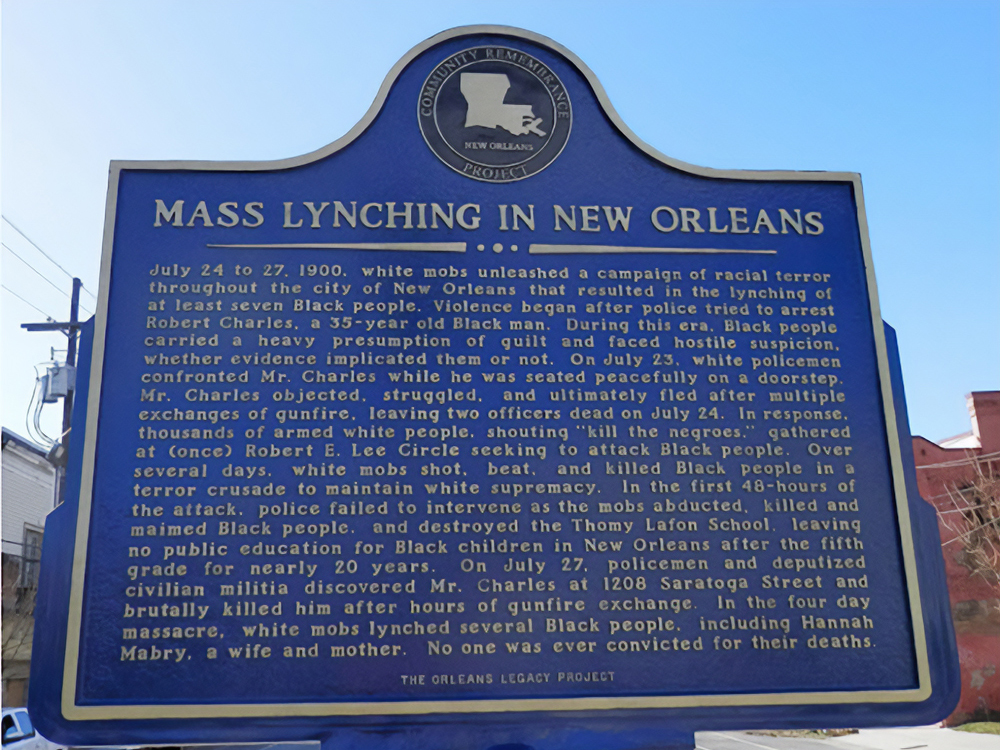

Those Black landowners who chose to stay behind became targets of racial violence, as white citizens attempted to force Black people off their own property. Among the worst of these racial terror tactics was the lynching of Black land owners.

“The Jim Crow caste system determined where you could eat, what platforms you stood on when you were catching a train,” says novelist Isabel Wilkerson. “This was a rigid caste system where any breach of the caste system could literally mean your life.” Before the Great Migration, 90% of Black Americans were living in the south. Afterwards, more than 50% were distributed throughout the United States. Migration was serious business for Blacks in the United States, participation could mean the difference between life and death.

Tired of segregation and fearful of lynchings, young couples in the Deep South like Robert and Genova Johnson married and moved to cities like Chicago, Detroit, New York and Cincinnati seeking a better life. There, they found better paying work as porters, hair stylists and construction workers and sent money back home to help their families. —Photo Courtesy of Genova Williams

Image courtesy of

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library

Exodusters

Migration for the sake of safety was not foreign to the formerly enslaved or free people of color and the early to mid-1900s was not the first time the formerly enslaved had chosen to migrate.

The Homestead Act of 1862 was a precursor to the Great Migration. The Act allowed all Americans, regardless of gender, race or birthplace to purchase and develop up to 160 acres of land. Black citizens took advantage of this opportunity, leaving or exiting states such as Alabama, the Carolinas, Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana to claim land in places such as Oklahoma, the Great Plains and Colorado.

?

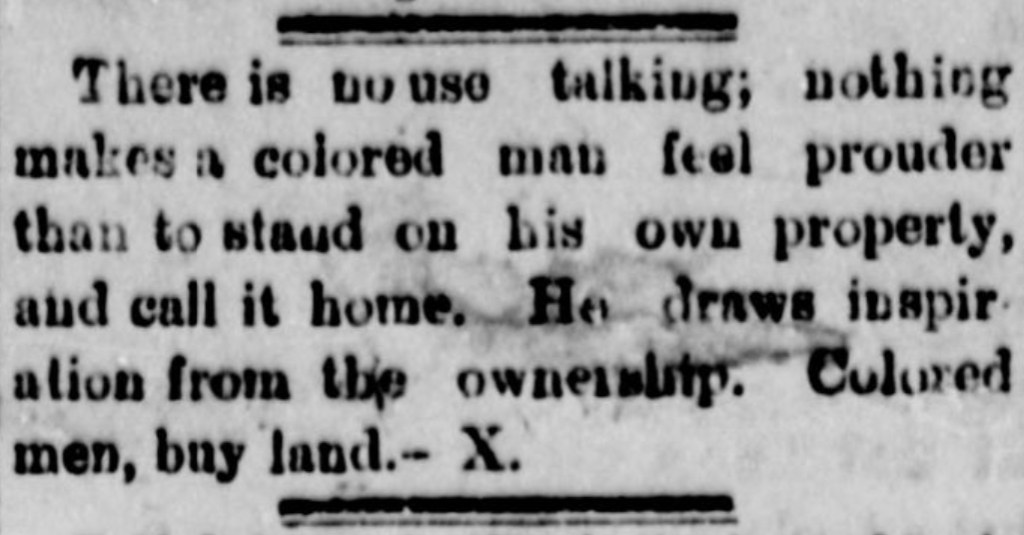

Editorial featured in the Langston City Herald, November 17, 1892

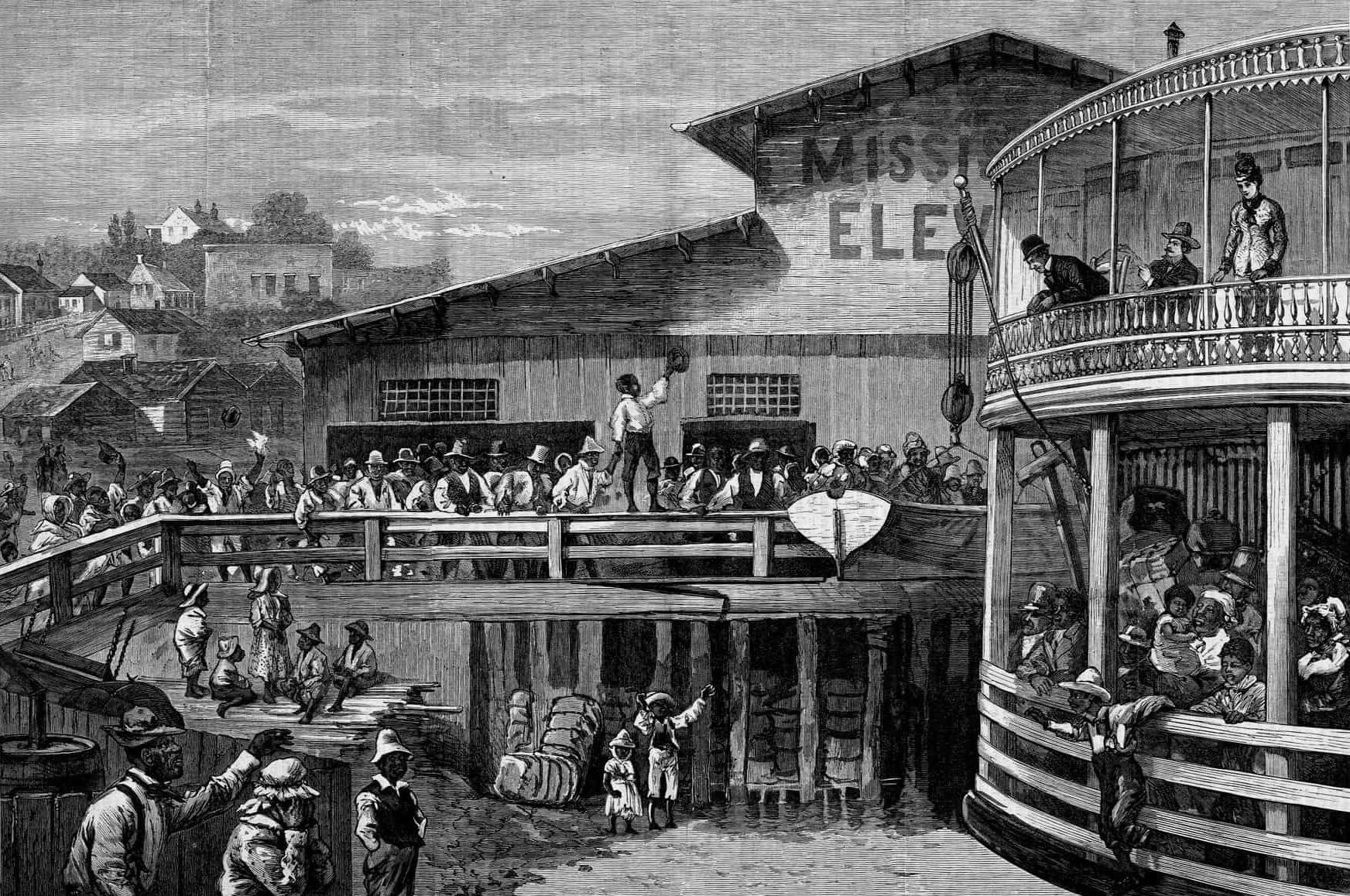

“In the spring of 1879, thousands of colored people, unable longer to endure the intolerable hardships, injustice, and suffering inflicted upon them by a class of Democrats in the South, had, in utter despair, fled panic-stricken from their homes and sought protection among strangers in a strange land. Homeless, penniless, and in rags, these poor people were thronging the wharves of Saint Louis, crowding the steamers on the Mississippi River, and in pitiable destitution throwing themselves upon the charity of Kansas. Thousands more were congregating along the banks of the Mississippi River, hailing the passing steamers, and imploring them for a passage to the land of freedom, where the rights of citizens are respected and honest toil rewarded by honest compensation.”

— Report and Testimony of the Select Committee of the United States Senate to Investigate the Cause of the Removal of the Negroes from the Southern States to the Northern States, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, S. Rep. 693 (3 parts), p. x.

The Negro exodus – Scenes on the wharves at Vicksburg / from a sketch by James H. Moserm 1879. Library of Congress

Forty Acres and a Mule

Some former slaves were able to acquire abandoned land after Emancipation; others were able to purchase land and gain a true sense of independence. While land ownership was a step forward in economic stability and planning for their future, it was also about preserving their past. As a result, many formerly enslaved persons chose to remain in the area of their enslavement for many generations.

Some became landowners when the government redistributed some 20 million acres, mostly in the south, under the Homestead Act. Three years later, Union General William Sherman famously promised formerly enslaved people “40 acres and a mule.” In January 1865, Sherman and the abolitionists Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, who had been actively advocating for land redistribution, met with twenty African American leaders who told him that land ownership was the best way for Blacks to secure and enjoy their newfound freedom. On January 16 of that year, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, reserving coastal land in Georgia and South Carolina for Black settlement. Each family would receive forty acres. Later, Sherman agreed to loan the settlers army mules. Six months after Sherman issued the order, 40,000 former slaves lived on 400,000 acres of this coastal land. Then, less than a year after Sherman’s order, President Andrew Johnson intervened to confiscate a vast majority of the land freedmen had settled and returned it to its former owners.

“Twins Elsie (1889-1981) and Lela (1889-1962) Scott were two of seventeen children of Exodusters John and Julia Scott. The Scotts migrated from Louisiana to Indiana and then to Stafford County, Kansas. This photograph was taken at the W. R. Gray Studio in St. John, Kansas in 1910.”

– Digital Public Library of America

The Exoduster movement was so popular that in Kansas alone the Black population went from 627 people in 1860 to 43,110 people in 1880.

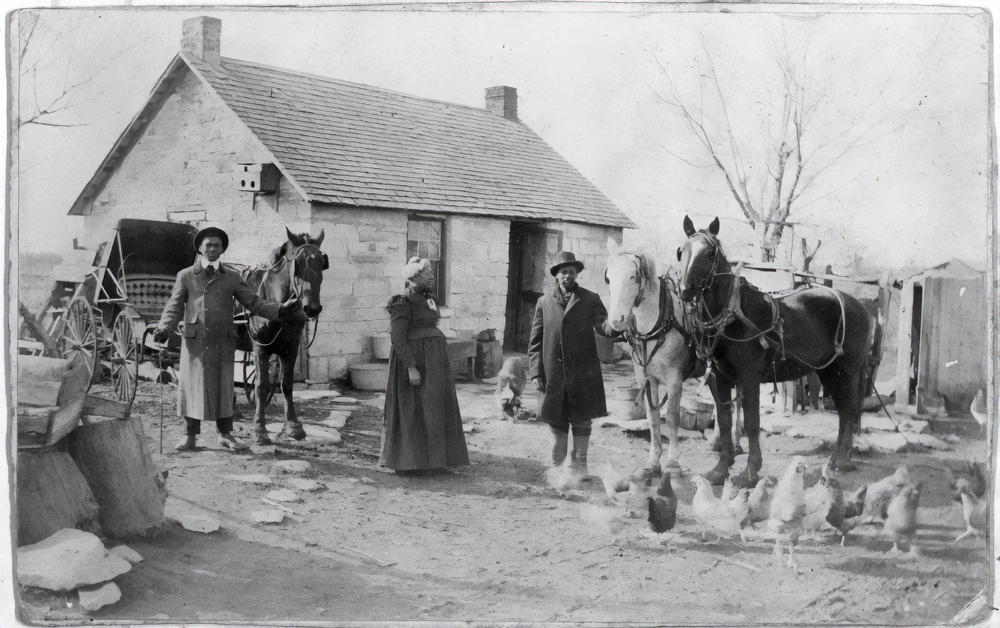

Kansas Historical Society: This black and white photograph shows John Summer and his family standing in front of their home located two miles northeast of Dunlap, Morris County, Kansas. The home was built in the 1880s.

How a Kansas town became one of the nation’s first majority-Black farming communities

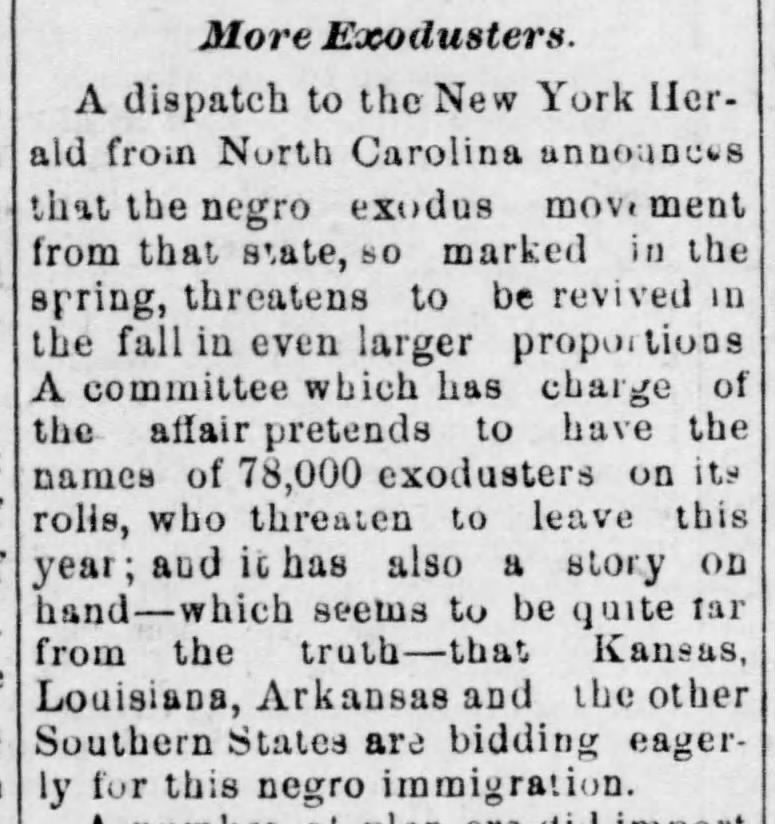

More Exodusters: The Pulaski Citizen

Pulaski, Tennessee

Thursday, Aug 15, 1889.

Welcome Negro Business Men:

The Topeka Plaindealer

Topeka, Kansas · Friday, August 16, 1907

Source: Marion County Record

Marion Centre, Kansas · Friday, April 25, 1879

Reflection Questions

- What were some of the factors that caused formerly enslaved and their descendants to flee the South during the Great Migration?

- Why was it important to Exodusters to purchase land of their own during the Homestead Act of 1862?

Additional Resources

Lesson One: Legacy of the Land

Take a journey with QUEEN SUGAR‘s Bordelon family and follow their generational fight to keep the land of their forefathers.